CONTENTS

CONTENTS

Scroll 2

<Previous Next>

OUT

(continued)

![]()

Vassal considers his invention a gift to us all, to make of what we will. He also considers it an experiment, his own and everyone’s. He recognizes that in our various ways we will use it to study our world and ourselves. We will configure that study to suit our interests, and will draw conclusions that we may act upon.

Many of us, probably most, will use his invention often, to pursue our pleasure and advantage. We will spy on people who attract our attention, including family, friends, neighbors, colleagues, employers, competitors, and strangers. We will follow public figures around, including entertainers, celebrities, politicians, and star athletes. Whether on a whim or with prior intent, we will enter people’s homes, workplaces, and anywhere else, and stay there as long as we want. We will attend any occasions we wish, public or private, including anyone’s performances, exhibitions, celebrations, trials, meetings, medical appointments, counseling sessions, parties, and lovers’ trysts. We will not need invitations, passes, tickets, or anyone’s permission.

We will practice and be subject to surveillance of every kind, from voyeurism to espionage. We will develop a sprawling sense of omniscience, combining our own with everyone else’s. Often, we will feel vulnerable, sometimes victimized. In our every word and action, we will take into account not only what we observe using Vassal’s device, but also what someone else—perhaps many someones—may see and hear us say and do. Longstanding boundaries among us and within us will disappear. Taboos will be trampled. Barriers will fall. We will come to feel that we are all everyone’s intimates.

Vassal will enjoy seeing that play out. So will I. But I will also feel anxious, for his sake, mine, and everyone’s. Even now, at times, my anxiety knows no bounds—about many things, but particularly this matter. People’s use of his invention will influence, often determine, their health, happiness, prosperity, even their survival. That disturbs me.

He decided a year ago to turn his invention loose. Since then, certain questions have burned within me: Why is he releasing something so powerful, and to everyone, without restriction? Why is he exposing us to so much possibility and uncertainty? And why is he releasing it now, a generation after he conceived and developed it? What has got into him—what spirit, idea, desire, or need? Does he think he is helping people? Yes, somewhat, I suspect. Is he curious, testing everyone’s nature to see what happens? Some of that, too. And, more than benevolent and curious, as he is, and free of will, as he describes himself and often seems, is he also doing it just because he is doing it, venturing with the rest of humanity into an immense and intriguing unknown, but without hope, fear, or expectation? Yes, a great deal of that, I believe.

In the hours ahead, those and similar questions about Vassal will arise in many people. Many will try to get a sense of him as a person. They will want to see how he looks and behaves these days. They will want to know what he thinks about what he has now done. They will want to understand how, if at all, he justifies his deed. Many of them, I expect, will use his device to visit him here in Maine. They will come by the hundreds of thousands, maybe more. Their devices may surround us like a mist, or swarm about us like flying insects. I don’t look forward to that with pleasure.

But most people will not visit us. Instead, they will use their devices to attend to their more urgent interests. Meanwhile, everyone will wonder about him, though. They will follow media reports about him. Reports by people and media organizations who do visit him will spread everywhere. Countless people will scrutinize those, and form impressions of him. What will they think of him? And what will they think of me, his companion and scribe? And, of particular concern to me, what will they do about us?

I, of course, already have impressions of him, born of my years of friendship and collaboration with him. They include his impressions, too, of himself and much else, which he has described to me or which I have surmised. I have become familiar with him. In many ways, in fact, I am more familiar with him than I am with myself, and more objectively. At times, I can sense his unspoken thoughts, and envision his memories. I have enjoyed that—diving for pearls, as it were—though sometimes, as I say, my intuitions and discoveries concerning him trouble me.

* * *

Many people know how Vassal looked decades ago, but not how he looks now. I will take a few moments here to satisfy their curiosity. As I describe him, I will share my perspectives, which may deepen people’s understanding of him. My description will also spare some people the time it would take them to watch broadcasts about him, or to fly their devices to our hideaway to see him for themselves.

Like all outward appearance, Vassal’s is both a shell that reveals little and an emanation that reveals much. He is still a slender six-foot-six; probably an inch or two shorter than that now, actually, due to normal slumping and shrinking with age. In addition, the murder of Victory years ago has not ceased to weigh upon his body as well as his spirit.

His arms dangle, like those of many tall people. When he and I stand beside each other in the boat, they bump against me. Long as they are, his upper and lower arms look like poles strung together. But they still have plenty of muscle on them; he can flip a twenty-foot canoe onto his shoulders as easily as when I first met him, when he was a young man.

His wrists, too, are rugged. They stick out from his shirt cuffs like two-by-fours. His hands spread from there. Their thick palms remind me of old-fashioned baseball mitts. So does the skin on their backs, which is dark and leathery from days spent outdoors with me. And beneath the skin, his veins, tendons, and metacarpal bones run like steel cords.

His fingers show finesse. They taper to soft points, like dinner candles, and have lost none of their nimbleness. He remains adept at precise tasks like soldering tiny electronic components at his workbench, or tying fishing flies onto his line, even when our boat is rolling in the waves.

Unlike many of us aging mortals, including puny ones like me, he has not put on weight. His shoulders are square but narrow. When he is bare-chested or wearing a T-shirt, you can see his ribs and shoulder blades. Tall as he is, they exhibit a chinalike delicacy, seeming more fragile than they are.

His stomach is flat and hard, and his thighs and butt are lean and tight. His legs, like many tall persons’, stretch improbably, and look so skinny that at times they seem more like stilts than living appendages. But his body is proportionate and his shape pleasing, at least to me. He still looks good in jeans.

His feet, like his hands, are large. When he walks or runs, even barefoot, he looks like he is wearing small snowshoes. He isn’t clumsy, however. I’ve never seen him stumble, even when he is hurrying along rough trails in the woods or up a mountain. He carries himself easily. He moves with a swinging grace, like the basketball player he once was.

His neck is gaunt and sinewy. Its skin, like that of his hands, is ruddy from the sun but smooth as ivory. It tilts forward more than it did, having settled over the years. Perched atop it, of course, is his estimable head. Because of his height, his head seems compact, even small, but thanks to the boldness of his jaw and the expanse of his brow it is as handsome as ever. His face, eyes, and profile, once familiar to many people, look much as they did. His face, however, looks its age: more lived in, its planes flatter and sharper, as if split from stone. Wrinkle lines bracket his mouth, and more straggle across his forehead and around his eyes.

A stubble of beard still covers his cheeks and jaw. The brief curls are sparse as ever, but white now, no longer brown. His cheeks are more sunken, and convey that look of stone. In certain light, his face appears spectral, a mask, but it never looks scary or vacant. Most of the time it glows like a happy child’s, alight with his humor and intelligence.

The weave of hair that crowns him has become as white as his beard. It has not thinned, and he has allowed it to grow. It spreads beneath his cap, its fine tendrils curving outward. Older readers may recall that when he worked as a scientist and engineer in Boston, and for years afterward, he kept his hair well trimmed. Behind his head, it lay on his shirt collar as straight and clean-cut as bristles on a brush. Now, long strands of it entwine, falling across his shoulders and down almost to his waist. The strands are filaments, soft as silk. On windy days when he and I are on the river or walking along the beach, they stir and toss like telltales on a mast.

Mind, in its quest for limit and equilibrium

Mind, in its quest for limit and equilibrium

Past the fort, Vassal and I glide in stillness, suspended beneath the canopy of stars. If it were not for the slight rippling of the water around us and the shifting shadow of the receding shore, I could believe we were standing on land, on the porch of his cottage, looking through the trees to the river.

I tilt my face up and look at him again. During the decades I have spent with him, I have looked at him countless times and considered him from countless perspectives. Sometimes I think I have seen all that there is to see of him. But I know better. He changes. We all change, of course, but he—.

I still see only his silhouette against the stars, no detail. Then, as abruptly as a thought coming to mind, I see more. In a flash, the darkness around him lights up, luminous. The wisps and tumbling locks of his hair become traces of explosion too brilliant to look at. They fly outward like rockets, and scald the air. He is a bomb going off! I see him as never before. I realize for the first time that his mind, in its quest for limit and equilibrium, has always been exploding like this, in a single, prolonged blast: KABOOOOOOOM!

The vision passes. The darkness thickens. Vassal stands beside me as before, unharmed and unperturbed, seemingly unaware that anything has happened. I open my mouth, gasping. I must have been holding my breath. I inhale until my lungs seem to contain all the air around me. I exhale: “Whew!”

I breathe in and out, recovering. Or I may never recover. I have made it this far, survived to this point, but an end may be near, maybe the end. Vassal’s invention and its explosion are about to reach everyone. I have been happy about that, but only somewhat. Now, more than ever, I mistrust that happiness.

I have made it this far, survived to this point . . . .

I have made it this far, survived to this point . . . .

* * *

The force of what Vassal is delivering to the world tonight has not been evident to anyone: not to our government protectors, who, though attentive, have not suspected it; not to his friends, the Bigheads and the Indians, though they have been hoping for it; and not to me, despite my constant witness. Nor has it been apparent to Vassal himself. He would have told me. It has remained dormant within him, where he and Victory banished it years ago, in September of 1979, in the ceremony that took place soon after Victory’s and his last scandalous show.

That show was the second of the two they staged on successive evenings in a town a few hours’ drive upriver from where we are drifting tonight. The first show was his invention’s public debut. Word of his invention had not spread, so only a few hundred locals and several dozen government officials attended. In the event, a troupe of Bighead men, women, and children—short, stubby, and preposterously acrobatic as always—performed an impressive warm-up act. After that, Vassal and Victory demonstrated his invention, as the Journal describes.

By the time of the following evening’s show, word was out. Thousands of people came, from miles around. Much of the rest of the world, no doubt including readers of this book, watched on television. I was in the live audience. (I was not yet Vassal’s associate; I began working with him a few years later. I lived nearby and rushed to attend.) When I saw his device in action, it did not alarm me. Nor did it alarm anyone, as far as I could tell. There were no explosions, real or imagined, and no sense of danger. I recall people’s fascination, and my own, as we watched. Many of us fantasized about what we would do if we had one.

* * *

The ceremony I have mentioned took place on the river one misty morning several weeks later. There was not much to see, but the occasion was momentous because everyone believed that it put an end to Vassal’s invention. Once again the world was there. More than thirty thousand people, including me, gawked from the riverbank, and almost everyone else on the planet stopped whatever they were doing and watched on TV.

The ceremony was simple. Vassal and Victory paddled their canoe briskly to midstream, where they stopped and drifted. Vassal put down his paddle, picked up a curl of birch bark he had brought with him, pulled a vial from his shirt pocket, and shook his last little device onto the bark. Then he reached over the side of the canoe, set the bark on the water, and, with a cigarette lighter, ignited it. He nudged the burning bark with his fingertips. It spun away from the canoe, into the current. The flames flared, inches high, visible to the cameras and, as a point of light, to those of us observing from the shore. Within seconds, the device melted. For a few minutes, Vassal and Victory watched the smoldering bark float off downriver, then they paddled back to shore.

As they beached their canoe, members of the press engulfed them. Vassal stepped out and confirmed that he had destroyed his invention.

“It’s gone,” he said. “You can consider its saga ended. Eventually, someone else will invent something like it and make it available to people, but I won’t be that person. I’m done with it.”

* * *

Everyone knew that it could not be totally gone, because he could not have destroyed the knowledge that was within him. Some day in the future, if he wanted to, he could rebuild his device. But he said that he would never do that, and he sounded certain. Everyone, including me, believed him. And for all the years since then, he has held to that claim. That was the last anyone has seen of his invention, and the last most people have seen of him.

He told me once, “That morning, with everyone else, I watched that piece of bark float downriver with the remains of my invention onboard. As you may recall, the bark entered a riffle and flipped over. I envisioned that little blob of melted plastic and metal tumbling down through the current.”

He was familiar with that section of the river, from fishing in it. He had been accustomed to thinking of it as a place where trout and other wild creatures lived, where now and then mergansers swam around on the big eddies, or deer or moose came to drink, or raccoons sidled down to catch crawfish from the shallows or to rake out freshwater mussels. Rocks lay on the bottom amid sand and silt. On the surface, logs, branches, twigs, and leaves floated until they drifted ashore or became waterlogged and sank. Such was the usual life of the river.

“There went my last device. Back home, I had destroyed the others, along with my prototypes, materials, documentation, and the tools, molds, micromachining system, testing stations, and so on that I’d used for building it. I cast off everything I had done, all my years of work, which had been so much a part of me. That left an absence in me. It felt like it does when you break up with a longtime lover. The love continues and pulls at you; less and less as time goes by, but it keeps pulling and never quite stops. You know how that is.”

At any time thereafter, he could have geared up and reconstructed his invention. But he had no desire to do that, and never seriously considered the possibility. As far as he was concerned, his invention was dead and gone, as he had intended. It lived only in people’s memories and, to him, as part of the river.

“Now and then I thought about it, of course. How could I not? I thought of how it must have settled into the bottom sediment of the river, or maybe been carried out to sea. And I thought about that little birch bark funeral vessel, which probably bobbed along upside down until it sank or drifted ashore.”

* * *

Years ago, many people, including the Bigheads, the Indians, and me, hoped that one day he would retrieve his invention from within him and let the world have it. We believed that a healthy new balance might result, and that little enough harm would come of it. But none of us thought that he would actually revive it.

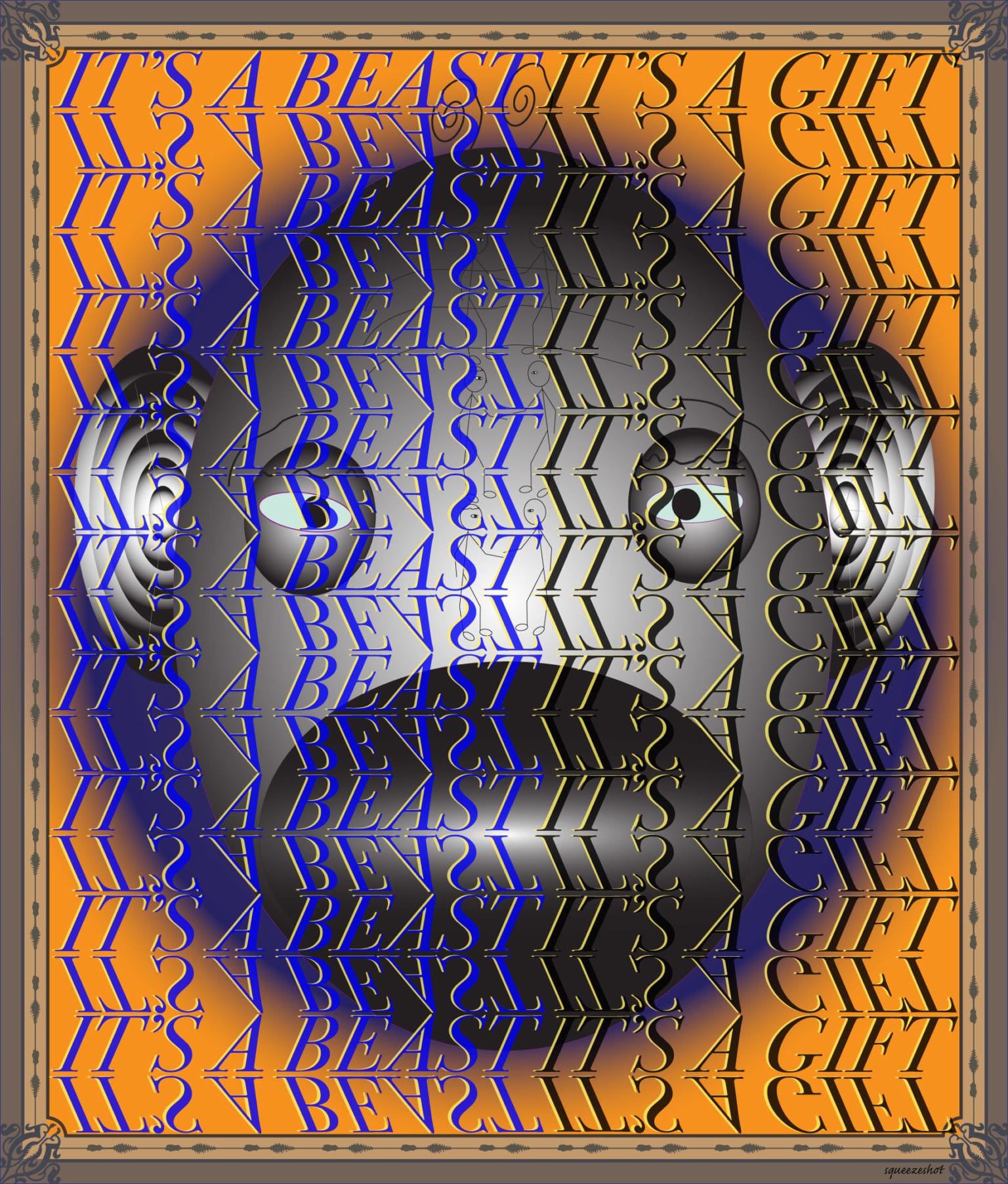

Now he has brought it back. Starting today, people everywhere will look around and know that it may be perching, hovering, or flying nearby, watching and listening to them, broadcasting to someone or many someones. It will enter every sanctum and enhance every view, prove any fact doubtful and any tale untrue. A creature of many minds, it will soon be so ubiquitous, and do so much for so many of us, that we may be unable to describe it, or to call it anything.

* * *

A beast to some is naught to others. Vassal believes that at worst, for most of us, the beastliness of his invention will become negligible. We will not find people’s spying intrusive. We will not mind people using it to their advantage. Each of us will hold our own with it. It will change our lives and our society, to be sure, but fears that we may have about it—about violations of our privacy, threats to our security, and other breakdowns of self and community—will prove overblown.

Many of us, of course, will think that we have much to lose: our relationships, livelihoods, property, etc. We have invested much in how things have been until now. We have depended upon certain institutions, and have benefited from traditional constraints: rules, regulations, procedures, codes of conduct, manners.

All of those will change. Many of us, no doubt, will try to defend ourselves against that change. Vassal has told me, however, that any defenses we attempt, whether legal, ethical, or technological, will prove futile.

He has said, “We may try to seal off our rooms, homes, offices, and other spaces to keep it from entering. We may sweep ourselves and each other using electronic instruments that can find it in our clothing, hair, body cavities, luggage, and so on. We may devise sensors that can detect it whenever it is turned on and seeing, hearing, and transmitting. But none of those measures will succeed. They will be too few, too inconvenient, too expensive, too unreliable, and too easy to overcome. Everyone will have to accept it and let it happen. Soon, people won’t even try to defend against it.”

What, then, of the trouble it may cause? What of the violence it may do to truths that we know and beliefs that we hold? Those may seem to rest firm, but are merely fictions that live among us. Things change. For instance, pages that I create may continue to resonate, applying their words, illustrations, and spaces between, but they do so only for a while. Soon, whoever reads them forgets about them and moves on, to travel other paths.

Some readers of this book will make every word and image in it their own. Others, more hurried, will skip through and try to extract its gist. Others will pay it little or no heed. They will turn away from it, or pass it by, or remain unaware of it. No one, however, will be able to ignore what it is about. Vassal’s explosion will have lasting consequences for everyone.

* * *

Some technological advances, when new, may seem to threaten us. However magical and useful they are in some respects, we regard them with ambivalence, at best. They settle in, however. No matter how problematic they may have seemed, we become accustomed to them. We adapt to them, adjust our attitudes. We end up feeling that matters have not worsened, may even have improved.

So it will be with Vassal’s device. What he is delivering does not foreshadow the end of the world, or even of our civilization or species. It is not bringing a severe epidemic or radical change of climate. He has not sent some mass of interplanetary stone, big as a mountain, to plow into the Earth at tens of thousands of miles per hour and obliterate us all. During the billions of years of our universe’s ramble, good enough has always come our way. For us, that’s life. We cannot be sure that will continue, of course, but we can reasonably expect it to.

* * *

We live in unresolved motion, amid flow and flux. Uncertain, ever in need, we look forward because we must. We look forward with hope. We can know only as much meaning and direction as our hope allows. Hope, change, direction, purpose, intention, desire, hunger, ambition—all describe facets of the same dynamic, our essential creaturely conceit, moving toward objectives. Without that dynamic, we would not exist. Absent that dynamic, we do not exist.

So Vassal observes, a perspective of his that informs everything he thinks and does. In his experience, all things that we are aware of are separate things, as we recognize, but also one thing, and also do not exist at all. In his view, all forms are at once material, immaterial, and formless, utterly beyond our ken. That includes matter of all kinds, as well as our thoughts, ideas, beliefs, feelings, sensations, intuitions, imaginings, and other perceptions. Each entangles every other in a singular manner as spooky as quantum duplicity. Each arises in our awareness like every other, resembles and reflects every other, and contrasts with and defines every other. Each—arising, resembling, reflecting, contrasting, defining—changing at every moment, resolving but never fully resolved. In that regard, each serves an identical purpose for us, and possesses identical meaning; each, though unique and distinct, is every other.

In his view, our points of awareness are buzzy bundles that wink in and out of existence. They come one after another, as different as can be. At the same time, they come many at once, simultaneously disparate and identical. Notwithstanding all difference among and between them, they come as one—pure, simple, infinite; unitary and coherent while also immeasurably complex and incomprehensible. And they are also entirely absent, an absence without dimension or significance. They exist for us and also do not exist. They do not and cannot add up, either to one thing or to more than one.

regard for meaning

regard for meaning

In less

than an instant

the ring of a bell

born of silence

delivers meaning

that neither begins

nor ends

ceremony

ceremony

Vassal’s and my drift tonight continues the ceremony of more than thirty years ago, when he destroyed his invention. I have inherited Victory’s place. He and I are looking ahead together toward the future. We do and do not know what to expect. The return of his invention is imminent, but not as before. Last time, he and Victory kept it under their control. This time he is turning it over to everyone everywhere, unconditionally, to use however they will. That is a radical difference.

During my decades with Vassal, I have seen little possibility of his invention’s return, and no likelihood. He has scarcely mentioned it. Signs of it have been obscure, nothing to make me suspect that he would resurrect it and let it fly. For the past year, however, his friends and I have known that he was going to do that. He told us. They were pleased to hear that. I was not; I was dismayed. But soon I joined with them, to help him launch it.

My dismay about what he is doing comes and goes. As I stand beside him here in the boat, the explosion that I envisioned minutes ago continues to disturb me. All of us, including him, may have underestimated the power of his invention. I wonder what he is thinking. Does he sense the immensity of his deed? In the darkness, I cannot see his face well enough to read his expression. I imagine the blade of his nose, the cool of his skin, his thin smile poised in thought. We have planned to drift until sunrise. But aside from that expectation, I do not know what may occupy his mind—what line of reason or cloud of indeterminacy. He has not told me, and I will not ask. I will remain silent as usual, harboring my thoughts.

He may be mulling refinements that he could add to his invention. Now that he is releasing it, it is too late for that, he knows, but he is ever the engineer, modifying creation. I feel the same about my work. For hours a day, I sit hunched at my laptop, engaged with my words and images: creating them, revising them, working to put them right. Every moment brings me the pleasures and challenges of fresh perspective, and sustains my wish to find and express more, to seek and share the pearl. In that respect, he and I work similarly.

In this matter, however, anyone may ignore what I do. Despite the significant task Vassal has given me, and the years that he and I have worked together, my role is peripheral to his. As a writer and visual artist who records and elaborates his saga, I deliver ideas into the air and notions into the passing stream. He, on the other hand, with his every thought and action, tinkers with the fate of humankind. Moreover, he has been doing that without intention and—unlike me at my work—without fuss.

His attitude reminds me of Ernest Rutherford’s buoyant reply when a journalist asked him why he and his students sought to split the atom for the first time. He said, “We are rather like children who must take a watch to pieces to see how it works.” Vassal is as driven as that, and as playful. Things are alive to him, and he responds. They nudge him and he nudges them back. He and they dance along, together and apart, like children at play or sweethearts in thrall.

A remark of John Cage’s, perhaps more obscure, also applies: “We take things apart in order that they may become the Buddha.”

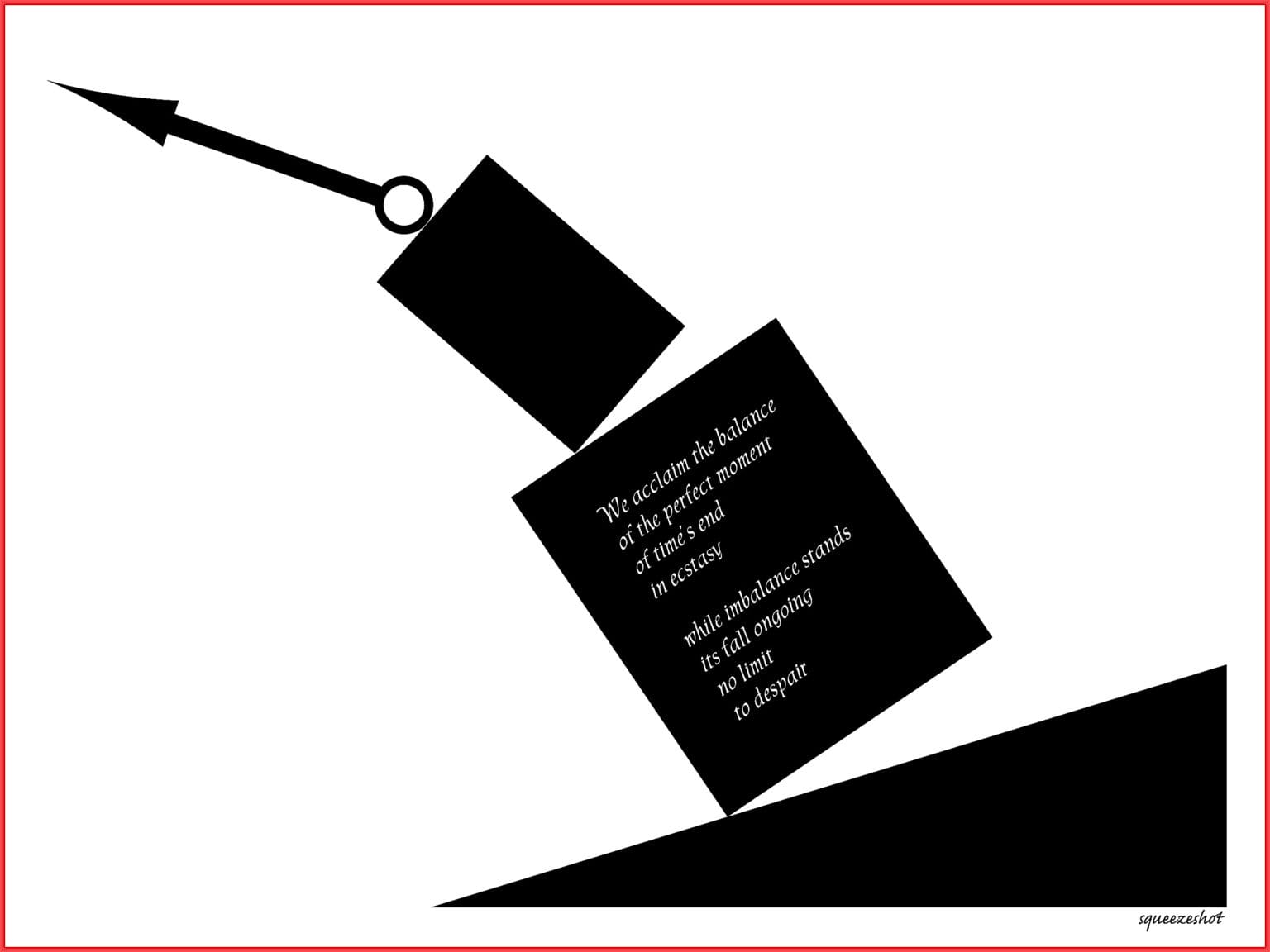

Vassal says, with equanimity, “People will like my invention. They will also suffer. The usual balance and imbalance will apply.”

We acclaim the balance

of the perfect moment

of time’s end

in ecstasy

While imbalance stands

its fall ongoing

no limit to

despair

* * *

Notwithstanding my unimportance compared to him, some readers will want to know more about me. Who am I, and how did I get involved in this? I will answer somewhat, and in the process disclose more about Vassal, which will be of greater interest.

The murder of Victory back in the 1970s did not surprise anyone. There were many possible perpetrators, desperate characters capable of such violence. Some of them were furious that Vassal had destroyed his invention, preventing them from acquiring and using it. Others regarded him as a devil, and wanted to take revenge for what they regarded as his blasphemy for devising so potent a facsimile of divine omniscience and influence. Other people, more bloodthirsty, their spirits more shrunken, craved the thrill and notoriety that killing Victory and/or Vassal would bring them. Vassal recognized those possibilities, and understood them. Since then, he has never wanted to know who the killer was. And despite the efforts of people who did want to know, and still do, including police and intelligence services in many countries, no one has ever found out.

The murder shook everyone. Sympathy for Vassal poured from every quarter. But it never reached him. Before people even learned what had happened, he shut himself away in his downriver home, to live alone with his grief.

By the following summer, he had healed enough to resume looking outward. The mere existence of his invention had brought a turning point to human affairs, even though no one but Victory and he had ever used it. He wanted to come further to terms with that development, and with Victory’s death. He knew that people would want to learn more of his story than news media had reported. He decided to tell it from his perspective, revealing new details and describing choices that he and Victory had made.

He was well prepared to do that. A few years before, when the U.S. and Soviet governments had begun pestering him for his invention, he had begun to keep his journal. He had maintained it fitfully, but it had grown. By the time of his final entry, which he had written shortly before Victory’s death, he had filled several hundred pages. They told much of his story. They did not tell it well, he felt, but the basics were there. Now, he wished to finish his journal and publish it. He sought a writer who could help him. He found me.

* * *

I am The Reverend Professor Henrietta A., or so I will say. I was a stranger to him then, busy with my own life. I taught philosophy and religion at a nearby college. (I still do, several courses. The Journal is a text for one of them. This volume will be, too, if the course continues.) I was young then, in my late twenties, a few years younger than he. I was ambitious and not yet tenured. The position he was looking to fill would take most of my time. His journal would need much editing, plus additional research and reporting. He thought that it would take us six months to finish. I figured it would take more like a year. If I got the job, I would have to drop my teaching, or most of it, and get a leave of absence. That might jeopardize my tenure or otherwise impede my career. But more likely, considering his fame and importance, it would assure my success.

I became less concerned about that, however. The opportunity was rich in other ways. Vassal was a seminal figure. His accomplishments thrilled me. His new project intrigued me. So did his person.

He interviewed me in an office that he had borrowed on campus. He knew one of the senior faculty members in my department, a friend and mentor of mine, who had directed him to me and told me what the job would entail. I had often met with my colleague/mentor in that office, the first time for an interview for my teaching position. The office was typical of an old New England college, more traditional than my cluttered nest upstairs. The door, windows, bookcases, wainscoting, and other wooden trim were painted eggshell white. The ceiling was high, also painted white. The wallpaper bore a Federalist pattern, pale blue and green ribbons of vines and flowers, running straight from floor to ceiling. The furnishings included oriental rugs, black wooden alma mater armchairs, a burnished hardwood desk with a hooded brass desk lamp and leather-rimmed blotter on top, and, behind the desk, a brown leather swivel chair. On the walls hung a mid-nineteenth-century oil painting of Mount Washington, and three prints: the college chapel, a Currier & Ives of a racehorse kicking up his heels outside a stable, and the nearby town commons in the early 1800s.

My colleague kept his office neat. He used it for meetings with students and staff, not for study. There were no piles of books and papers. When I went there to meet Vassal, the only books not shelved decorously in bookcases were a dozen stacked squarely on a side table. I had written several books and was proud of them. I hoped that at least one would be in the stack, but none were.

When I knocked at the door, Vassal greeted me cursorily and shook my hand, reaching down with some effort. Gesturing for me to sit down, he turned and in two strides stepped over a corner of the desk and folded himself into the chair. He looked out of place, in part because I had never seen him there, and in part because he was so tall and famous.

He clearly did not feel out of place. He did not act uncomfortable in the least. He perched his elbows on the arms of the chair, and with his forearms and hands formed a high triangle; his long fingertips met beneath his chin. His dress was casual: a tweed sport coat over jeans, and a green-and-black checkered flannel shirt.

Our meeting lasted twenty minutes. At no point could I tell whether he liked me. He was cordial, but showed me no warmth. His manner was distant and soft-spoken—distracted, I thought. He looked me in the eye a few times, but without expression. Mostly he scanned the walls. He wore a half-smile; about what, I knew not.

Our conversation was low-key, almost lethargic. He uttered a few pleasantries about our mutual friend, then politely interrogated me. What was my academic background? What was my daily work regimen? Did I enjoy my writing? How did I go about it? He asked about my approaches to fact-checking and revision. If he had read a sample of my writing, he did not mention it.

He asked if I would have enough time for him. I could manage easily, I replied; I would reduce my teaching load and other academic obligations as much as necessary. Did I know his history? Yes, as much as was public knowledge. Did I have any problems with it? Not at all.

To conclude our meeting, he asked if I had any questions I wanted to ask him. From the start, I had felt star-struck, honored to meet him and intimidated by his notoriety. Now, I wanted to know him better. I was curious to learn what he would publish, what he wanted to tell the world. He had said nothing about that. I knew that countless readers would be as curious as I was about him and his history—so curious that if I got the job, many would envy me my position. But I did not want to prolong our meeting by asking about those things. I did not dare, and I doubted that he would disclose much if I did.

“No, thank you,” I said, “no questions.”

He stood up behind the desk, reached across, shook my hand again, thanked me for coming, and waited—impatiently, I thought—while I got up and left. He did not come to the door, behavior that I have since seen was unlike him.

* * *

I came away frustrated. I wanted the job, but I feared that I had not helped myself get it. I had answered his questions forthrightly but with no brilliance. I was afraid that I had shown too little understanding of the task, and too little enthusiasm. Disappointed with myself, I fell into a funk. That night, I sat alone in the kitchen of my apartment and made a list of the job’s attractions. I pondered them for hours, out of self-pity more than hope.

The attractions to me were many. They included the implications of his invention for humanity, the dramas that it had caused in high places, the boldness of his decisions about it, its awful consequence to him, his current desire to tell the world about it, and his need for a wordsmith like me. As I pondered them, I longed for the job. Even its dangers appealed to me. They portended battles that I wanted to fight.

I believed that I could help him. I knew that I was well qualified. In addition to teaching, I had chaired several conferences, moderated many scholarly discussions, presented many papers, and published dozens of articles and monographs. The books I have mentioned had been well received. They concerned nineteenth-century American philosophers, poets, and divines—Emerson, Thoreau, Dickinson, Henry Ward Beecher—whose lives and works I considered relevant to Vassal and his adventures.

My skills and inclinations were academic, not commercial. That, too, should work to my advantage, I felt. His journal was comprised of short entries, a patchwork. That structure should remain. His book did not want the fluency, drive, and polish of a popular best-seller. To the extent it needed filling in, as my mentor had said it did (no doubt because Vassal told him), it should not fill with familiar antecedent and cliché. It should not tease slick narrative out of complex reality. It did not need to coddle, flatter, or divert its readers, or deftly hold their attention from page to page. It need not entertain them.

Given his history, his readers would not care about any of that. News media had reported about his invention for years. Thousands of people had seen it in person when he and Victory had displayed it, as had millions more via TV. People knew about it and had strong feelings and opinions about it. They would read whatever he wrote.

He should want a writer of flexible mind, one who would present his story from the many perspectives it deserved. He should want a scholar who, while attentive to how readers understand text, would not feel constrained by customs of style and structure, or by orthodoxies of current literary theory. His writer should be unafraid to compose bloodless essay rather than dynamic tale, difficult prose rather than easy reading, contradiction and confusion in lieu of conventional good sense. Such an approach would tell the truth that would best serve him and everyone.

I built what I thought was a formidable case for getting the job, but too late, I knew. I made its points to myself, but felt certain that I would never make them to him. My interview with him had been a failure. He was done with me, no doubt, and had turned to other candidates.

* * *

A few days later, to my shock, he called me for a second interview. He asked if I could come right over.

“Of course,” I said.

I hurried to his office, determined to present my case. In the event, however, my self-assurance again abandoned me. I did not make any case. Once again, I felt that I could not act so forward. It would have been too self-serving. He would know best what he required, and did not need to hear my opinions.

I felt shy. That was not like me. Usually, I was not timid about anything. In classrooms and lecture halls, at conference podiums, in my writing, in my personal relationships, and in every other aspect of my life, I behaved with confidence. I was highly verbal; I spoke my views freely and, I felt, incisively. From childhood on, I had read insatiably and had loved to write. By the time I reached adulthood, I was not at all introverted. My reading, writing, and thinking drove my ambitions and enlivened my tongue, sometimes to excess.

But this person and his situation continued to intimidate me. I respected his past travails and I admired his radicalism. I sensed that though this project of his would mostly involve editing and ghostwriting for him, it held potential for more. It seemed risky in ways that I approved and wanted to be part of. No matter how worrisome or hazardous it might become given his history and circumstances, it would be work that I believed in.

I wanted the job desperately. I did not want to blow my chance of getting it. But, as I say, during that second interview, as during the first, my nerves got to me. Again I failed to promote myself. He asked me more questions, which I answered hesitantly and incompletely, using even fewer words than in our first meeting. My voice sounded small to me, nearly inaudible. It was as if I, not he, was the one emerging from trauma and isolation. Maybe I was, and maybe he represented my best hope for recovery. Or maybe I was under his spell, or under my own, put there by the device he had made, by what the world thought of it, and by what I believed it could do.

As I sat before him, those considerations turned in my mind, rendering me mute. This time, he had a copy of my Emerson book on the desk. I supposed that he might ask me about it, but he neither looked at it nor mentioned it. I figured that I was indeed blowing my chance.

That is all I remember of that interview. It was one of few times in my life that I came away from a conversation with no memory of what had been said, just a sense that I had failed to communicate what I should. For hours afterward, I could think of nothing except Vassal and his project—not my friends, not my work, not anything. I dwelt in faint hope that I had met his requirements and suited his vision, but I felt certain that my hope was in vain.

* * *

I did not have long to feel sorry for myself. The next day he summoned me again to his office. There, smiling warmly, looking me in the eye, he offered me the job. I was stunned. I looked away from him. I took a deep breath, as if I had not breathed since our interview the day before. I did not answer him. We sat in silence. To my surprise, I did not feel pleased that he had offered me the job, nor did I feel like taking it. I felt confused. My self-possession continued to elude me. I wondered if I was suffering from a mental condition or a brain disorder. I needed help or to rest, to regain my bearings. I envisioned a dazed trip to the college infirmary, maybe to a psych ward, or just back to my apartment, to spend some days in bed.

My heart’s desire had been to get the job. Now, with the offer in hand, I was not sure that I wanted it. I felt doubts, but none of them were specific. I could not formulate them. Most uncharacteristic of me, courteous as I usually was, I felt neither inclined nor obliged to respond to his offer. It was as if I was sitting alone in the room, as if he, the famous Vassal Squeezeshot, was not there. I sat unmoving, in a silence that might last forever.

It lasted only a minute. My thinking began to clarify. If I were to take this job, I would enter a peculiar situation. I would sit with this man, either in an office at the college or in his home downriver (I did not know which workplace he had in mind), and in addition to doing some original writing for him, and editing, I would take dictation from him and type for him, like a secretary. Depending on how he went about completing his journal, there might be more of that than I would like. Neither of us could know that in advance. I would embark on a process over which I would have little control, in which he would be the boss. If he or I made a mess of it, the result would be a book that might do no one any good, and that would give me a bad reputation.

Also, this man might prove difficult to work for. Given his history and the force of his personality, that seemed all too possible. He might prove to be too much less than sane, or too much more—too intense, either way. He was gifted, I could see, but aside from cohabiting with Victory for a few years, and working at an engineering firm before that, he had been accustomed to living and working in solitude.

Also, in the past year he had been profoundly wounded by circumstance. He might not have recovered. He might never recover. How might his recent trauma influence this project? If I were to take this job, there would be just the two of us, working together. Inevitably, that experience of his would come up and we would have to deal with it. How might that unfold?

Should I turn his offer down? Or at least, before accepting it, should I see if the college would allow me to return to full-time, tenure-track status if this job of Vassal’s did not work out?

* * *

I knew I had to answer him. Fortunately, my good manners returned. I wrote off my concerns as hesitations typical of me. I was less a worrier than I had been as a younger adult, but I fretted more than I should, as if that could somehow help me shape a better life for myself and a better world for all. Enough of that foolishness. This was a time for daring, for taking chances, not for wanting more foreknowledge and control of my life than life allowed. I replied to him, hoping to conceal the doubts that had delayed me.

“Yes,” I said.

My voice sounded so faint that I was not sure I was speaking. Or if I was speaking, I was not sure he could hear me. He kept looking at me, waiting, as if I had not said anything. I blushed—me, who never blushes.

I took a breath and spoke again: “Yes,” I said, “oh, yes.”

This time my voice squeaked, unintelligible again. I cleared my throat. My eyes jumped to his, then away. I tried to smile.

Then I spoke yet again, in a whisper: “I would be delighted.”

SCROLL 3 ➡︎

TOP⬆︎

CONTACT/SUBSCRIBE

(See the latest newsletter here.)