CONTENTS

CONTENTS

Scroll 5

< Previous Next >

OUT

(continued)

![]()

“I am no believer in God, or if I am then I believe that every phenomenon is God, including every creature and thing, every idea and sensation, no exceptions, none inferior to any other. If anything is God then everything is God.”

To Vassal, as I have said, no god but us creates or controls. In his view, ours is mind that thinks itself, that knows without knowing and is aware without distinguishing. Our every deed performs itself. We are at once creator and created, discoverer and discovery, mover and moved, cause and effect, subject and object. Alive in that way, all things possess infinite dimension and potential, and equal value.

To him, no gods are resident in Heaven but not Hell, or more embodied by angels who sing on high than by fallen angels who rule satanic depths. Figments of our imagination that they are, no gods are better or worse than any others, and no heavenly phenomenon better than any hellish awfulness. What we think is good is no better than what is bad, evil, or tragic. Nor do we love the good more.

We love the good, said Plato? He was wrong.

We love as well the wicked and the weak.

— James Merrill, in Matinées

Vassal would never assert that any god is better or more virtuous than another, or “more in me than in thee,” or “in this but not that,” or “here but not there.”

He says, “No god worthy of the name resides more in one time or place than in any other. People who think that the god they know is superior to another make a weapon of it. They think ‘God is on my side,’ or ‘I am a chosen one,’ or ‘We are the chosen.’ That may help motivate them, and make them feel better about one thing or another, but that thinking cuts as much against their interests as for them, and gains nothing. Victory and I saw that when we snooped around.”

The two of them determined that no cause that anyone might defend with his device, and no initiative that anyone might undertake with it, would change things for the better. None would be more beneficial than any other. To believe otherwise, as people naturally would, would lead to manipulation of others and righteous conflict. They wanted no part of that.

Regarding God or gods, Vassal’s perspective remains much as it has been for years. He would subscribe to two well-known maxims (variously ascribed): “God is a circle whose center is everywhere and circumference nowhere,” and “God is a comedian playing to an audience that is too afraid to laugh.” Those maxims suggest the scope and substance of his metaphysic. They inform his devout absence of conviction, his nonaggressive manner, and his ready sense of humor, and underlie his skepticism concerning people’s beliefs.

On the porch one afternoon a few weeks ago, he said this about the drama to come: “Many creatures, including us humans, live on both sides of the divide between self and other. That’s what suits us. It’s both practical and necessary for us. Otherwise we couldn’t live. When my invention comes and people use it, everyone will experience more of that. They’ll become more familiar with both sides, and with the divide, and with the ways in which there is no divide. That happened to Victory and me when we used it. Not that anyone will gain. It’s more of the usual, more of the same.”

I often think about his view that self and other are both separate and not. This time, as I wrote down what he said, I stopped for a moment and looked at my laptop. Is this machine me, as much me as it is “other”? And is it also both of those, one thing somehow? Self is It and It is Self? Is that possible?

He continued: “The idea that there’s no divide between self and other seems ridiculous, but only on the face of it. There’s only one face. It is everything and everywhere.”

He may have surmised my line of thinking, or I may have surmised his, or both—the one face facing, perhaps.

He went on.

“It is ridiculous, but also not ridiculous—not to me and not to many other people. To me, as you know, Reverend, all of us actually are every creature and thing, and they are we. That struck me years ago, as big as everything, and it has stayed with me. To me it’s obvious; no better or worse than anyone else’s reality, but obvious, not at all mysterious. I figure that’s worth our mentioning in the book. If it communicates anything useful to anyone, that’s fine. And if it doesn’t, that’s fine, too.”

He was doing his duty to our project, saying what was his to say.

“We humans are somewhat rational, able to form and use ideas that suit us. Our universe is something we make some sense of. We observe and describe things about it: facts, qualities, processes, possibilities. But just as it is almost entirely made up of what we call dark matter and dark energy, which we cannot perceive directly and which we know almost nothing about, we, too, are full of things we aren’t aware of, may never become aware of, and would not fully understand even if we were aware of them. For our species, complete understanding is an oxymoron.

“We are unaware of more than we can imagine, including zillions of things we wouldn’t have the least idea about even if they were right in front of us, which they are. And that’s fine. That works for us. Though nothing makes total sense to us, we get by.”

One thing makes sense

Nothing

Not even that

It is no object or idea

no location or absence

no question we can ask

no words we can use

It goes without saying

We have no shape to give it

no effort to

make on its behalf

There is nothing for us to

be aware of and that is all

We have no use for humility

We can take no pride in anything

“Here’s something else about that. It surprised me when I learned it. It’s that over ninety percent of the trillions of cells in our bodies aren’t us. They’re our microbiota, our community of microbes, mostly bacteria, viruses, and fungi. There are thousands of species living upon us and within us. Their body mass during our lifetimes adds up to that of five adult elephants. Most of what we poop when we poop is them, not digested food as we tend to think. They play a major role in our brain development, our behavior, and our diseases, including diabetes, obesity, asthma, hypertension, atherosclerosis, arthritis, bowel diseases, and a number of cancers.

“They have come to us from many stages in our evolution. They have found their ways to us through random selection, survival of the surviving, and other dead ends that haven’t died yet. Some of them hitch onto us when we are born; they come to us from our mothers’ wombs, and our mothers’ mothers’, and so on back to some mamas who lived hundreds of thousands of years ago. Others may have arrived when ancestor cells of ours ate them or otherwise became attached and kept on living. Many of them became parts of our bodies, and part of our genetics, while remaining more or less separate creatures.

“That sounds creepy, doesn’t it? It’s quite a heritage. But those critters have helped bring us about as a species; and as individuals, one birth at a time. They help sustain us before we are born, and afterwards. We couldn’t be born without them, and we couldn’t survive without them. Many of them depend on us for their survival, too. And many of them, as far as we can tell, are of no use to us or us to them. They just live with us, either inside us or on our skins.

“We incorporate other things into us, too: fluids, minerals, gases, and other biological and chemical building blocks and mechanisms. Many of those, too, are useful to us. We are quite some pieces of baggage, more disparate than we may realize. We carry around a huge number of things we can call both ‘other’ and ‘us.’ All are part of who we are and what we do. Such is the dust that we are, dust that has been coming our way since the Bang if not before.”

Again he stopped talking. I had several of his sentences left to transcribe, but this time I, too, stopped. I stopped writing and did not resume. I had never done that with him. He noticed. He may have supposed that I was thinking about something he had said, or about some idea I had come up with. He probably figured that I would return to my writing. But I did not. I did not even think of it. I had lost track of what I was doing. I do not recall what was in my mind. I suspect I was absorbing what he had said about the creatures who are part of us, and about how we and all things are dust that comes our way.

I folded my hands over my belly and looked at my laptop. It held no appeal for me. I did not want to touch it, much less write on it. I was tired of filling pages with Vassal’s words, fashioning them into stories with which to paper over the infinite void. Why should I flatter readers’ illusion—and often Vassal’s and mine—that each of us is a self who makes and understands sense; a self to whom stories can be told and things explained?

I did not want to continue that charade, not then. I knew that my memory was good. Later, if I wanted to, when I revised the day’s work, I could write down whatever Vassal had said that I had not transcribed. I could add words of my own then if I needed to, to fill any gaps. But would I? Would I get back to my writing at all, that night or ever? I did not know and I did not care.

* * *

That night I did catch up. I had no trouble remembering most of what Vassal had said, and I extrapolated the rest. It filled several pages.

Here is what I wrote:

This afternoon, seeing me stalled and disinclined to write, Vassal was gracious to me as ever. He acted as if there were no problem. He waited patiently for me to start again. When I did not, he resumed talking anyway, perhaps thinking that that would get me going. But I continued to sit there, not writing.

He stopped talking, reached to me, and squeezed my forearm.

“What I have been saying is philosophy, isn’t it?”

He was speaking in his most conversational tone.

“It is, sort of, don’t you think? From me, of all people. Who would have thought? It’s amateurish, no doubt, not that I would know. As you know, it’s not my cup of tea, not my education or profession and not what I’m usually interested in. It’s your field. You’re the reverend professor, not me. I hope that you don’t find my efforts too sophomoric. Do you?”

He paused, but only briefly. He knew that I would not answer him.

“I don’t think there’s any harm in my trying,” he said. “I should try, whatever my inadequacies. I can’t talk about my invention without philosophizing some, if only to encourage you to take it from there. I hope that as usual you’ll improve what I say before sending it into the world.”

He paused again, turned his head, and looked at me squarely, as if this time he expected me to speak. That look is a mannerism he uses with me sometimes. He does it partly to be polite, as if our work involves a spoken dialogue between us, which it rarely does. Mostly, though, as he said, he does it to point out topics to which he wants me to add my own thoughts and words. Almost always, when he does that, I say nothing in reply. Soon, he resumes talking, as he did on this occasion.

“I can see how people would appreciate studying philosophy, and talking and writing about it, and teaching it, as you do. It deals with questions that are fundamental to everyone. By addressing them we hope to increase what’s best in our lives and to mitigate what isn’t. We try to understand and express things that might help us. Isn’t that what it’s about?”

I still had not resumed writing. I looked at him evenly, which I rarely did. He was being more polite than usual. Was he trying to charm me into responding? His lips held one of his half-smiles. Returning my look, he raised an eyebrow, as if to cue me. I looked away from him, to my laptop, my usual refuge. He turned and gazed out from the porch, toward the river.

“Anyway,” he said, “it provides relevant material for our opus. I like to stretch my mind that way, open it up, though I’m not good at it. Maybe I shouldn’t do that. Maybe I open it too far. But that’s for our readers to judge. They can read my imperfect philosophizing and like it or not. Or they can skip it, or ignore it. Like my invention, it’s theirs to do with. It’s about them, not about me. Whatever they do is fine.”

“What I say is true by my lights, but not necessarily true for other people. My lights, like anyone’s, don’t shine everywhere. There’s always plenty that’s outside my view and beyond my understanding. It’s the same with anyone; I’m no different. I make no claims. I just speak as dust speaking to dust, as we all do. We’re debris from billions of years of cosmic explosions. The dust keeps settling. Some of it gets bound up for a while in chunks of heat and glow, humanoid in our case. At the moment, some of it is you and me sitting here: me spewing words, and you, maybe, getting ready to use your computer to clean up those words. Ours is a dusty business.”

Him spewing while I clean up? A dusty business? True by his lights but not necessarily by other people’s? Nice ways to put it. My mood was improving. I could hear in his voice that what he was saying to me pleased him. He loves coming up with verbal strokes and jokes like those. They emerge from him as many of his observations do: like virtual particles that simultaneously pop in and out of existence, at once delivering and withdrawing the consolations of form and meaning. Pop! Poof! They are here and elsewhere and—in the same moment—gone!

I like those strokes and jokes of his, too. They warm my reverend-professorial heart. If he did not come up with them as often as he does, I doubt that I would be here. He is somewhat a holy fool, with that smile of his always on his face and within him. I adore that.

* * *

That night while catching up, I continued thinking about his remark that we are dust that comes our way.

It was a variant of the “we are stardust” concept, wherein time, matter, and energy developed from the Big Bang; became particles, waves, fields, etc.; evolved (some of it) into elements, minerals, proteins, amino acids, RNA molecules, etc. that eventually became us humans.

Each of us comes of that process and continues for as long as we live. Meanwhile, more dust and energy in their myriad forms arrive and become part of us. Among our other transformations while we live, we shed and replace our bodies’ cells: 500 million skin cells each day, our whole outer skin once every few weeks, our sperm cells (in the males among us) every three days, our skeletons every seven years, and so on. That is in addition to our sloughing off the herd of elephants he spoke of earlier—our more or less symbiotic load of microinhabitants.

Then we die and shed our remaining cells and other matter, after which what we were continues in other forms and also, in Vassal’s view, as the eternal, formless form that continues as all dust does, we as it and it as we. Thus immortal, we continue to dream ourselves and all else. As he would say, that, too, is what we are and what we do.

![]()

Vassal’s invention will bring things nearer. They will become more familiar to us. Perhaps, as he suggests, they will also become more part of us, or seem to. Everything may prove to be reflections of us and also to be us—our consciousness at work, our perceptions at our service. Our use of his device may diminish or remove boundaries within and among us, or at the least highlight for us our commonalities.

It will highlight differences, too, of course. Many of those will remain, as many as ever. For our kind, as he says, difference is ineradicable, bound up in everything as yin is to yang, into a whole that both subsumes and embodies difference. His invention will not enable us to resolve that seeming paradox toward some better condition, some pure, eternal, comfortable, and unifying peace. We are not capable of that except in our imaginations, and there only briefly and imperfectly. Difference persists. For us, such are comfort, unity, and peace.

As we use his invention, many things that have differed may seem to combine, however, perhaps into a single fiber of infinite dimension. Or they may seem to recombine, reminding us of their unitary nature. We may address differences as if with a mantra, sounding and inhabiting the all-encompassing. We will perceive differences as always—between self and other, inner and outer, good and evil, etc.—but at times those differences will lessen or disappear, or seem to.

Our regard for other things intertwines with our self-regard. As we use Vassal’s invention, that may become more apparent to us. We may even consider the two simultaneous and identical, as he does. Studies in human perception support his and others’ observations that all things are creatures of our minds. Those studies cannot prove that, of course. No proof can prove itself. Such is science and, to him, all human perception and analysis: ever inconclusive, all questions open.

He likes that. He keeps informed about many avenues of research. He follows dozens of them assiduously, study by study, paper by paper, hypothesis by hypothesis. He values them less for the answers they provide than for their provisional, emergent nature. Sometimes, when he is reading a newspaper or scientific or technical journal (he reads almost fifty online), or when one of his friends reports some development to him (the Indians and several Bigheads are science and engineering mavens), he exclaims, pleased but without exultation: “Aha, more evidence from the endless supply!” Or words to that effect.

* * *

During the Renaissance, Venetians learned to coat glass with metal to produce mirrors that reflected with unprecedented accuracy. For a time, for many of us, the mirror that is Vassal’s invention will be similarly revealing. We will think that it shows us more of who and what we are. It will suggest new possibilities to us, and it will revive old ones that we have forgotten or abandoned.

We will try to bring some of those possibilities to fruition. That will not be easy. As with any look into a mirror, and as with all disruptive technologies, using Vassal’s device will prove difficult for us as well as effortless, challenging us as well as comforting us. It will display to us its limitations, and with them our own. We will sense how much it cannot reveal to us. We will find that there is as much as ever that we cannot see and may never see, enough to prove to us once again what we already know: that there is always more, everywhere, than meets the eye; more than we can comprehend. As many possibilities as ever will remain unrealized, and as many beyond our imagining.

“My invention will give us a good look at things,” Vassal says, “but an incomplete and imperfect one, ever changing.”

Look once

then look again

It is as it seems

but never as it was

As it seems and not

and neither more true

objects of consciousness : accidental harmony

objects of consciousness : accidental harmony

Cassius: Tell me good Brutus, can you see your face?

Brutus: No Cassius, for the eye sees not itself / But by reflection by some other things.

— from William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar

I have described how to Vassal everything we perceive, within or outside us, reflects and embodies us. All are umwelt, the self-bubble, comprised of all that we can know and more, including all that we can imagine. To him, our consciousness is itself imagination, our universe the object of that imagining, and our acts of imagination at once our own acts and everything else’s.

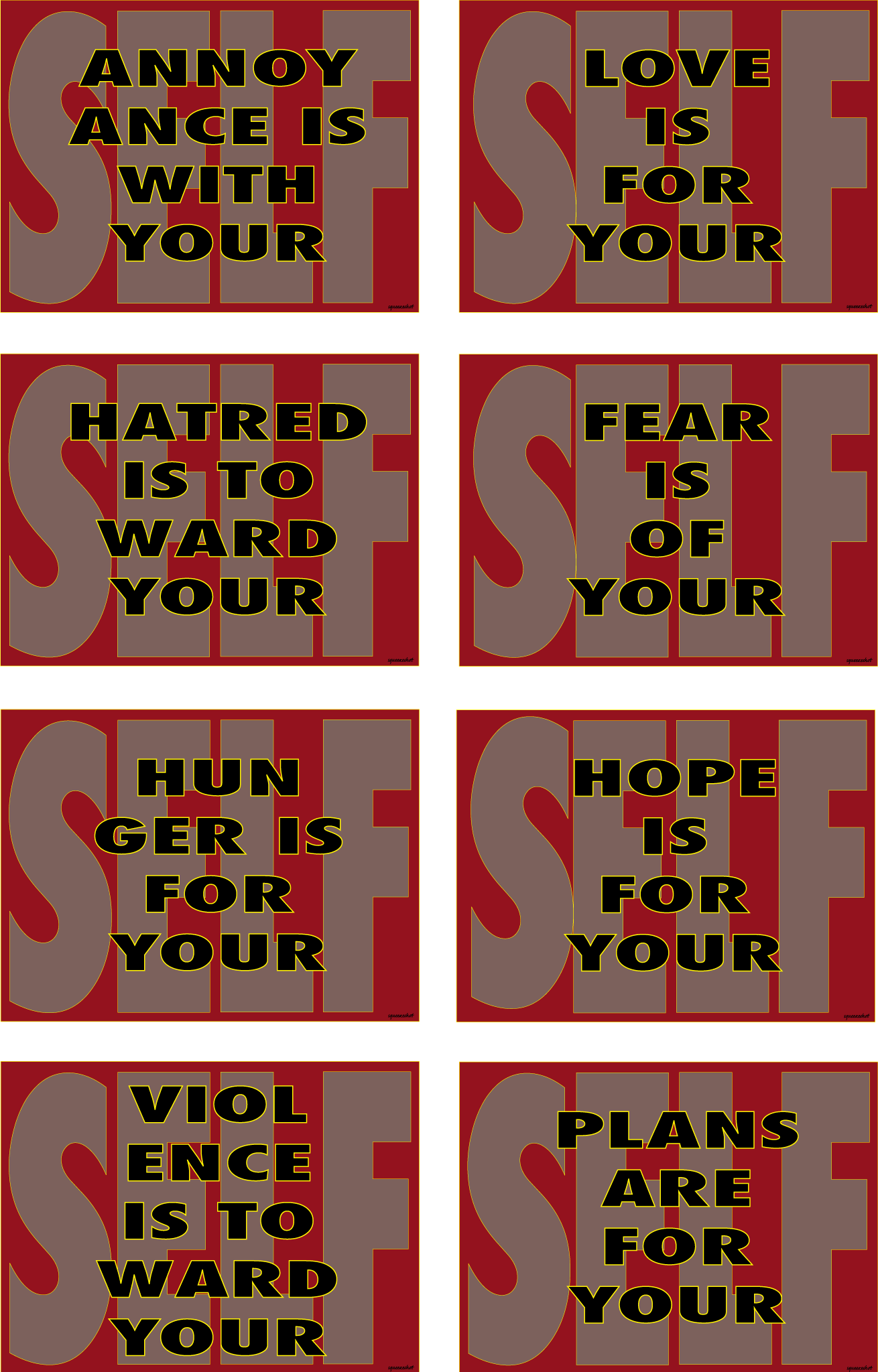

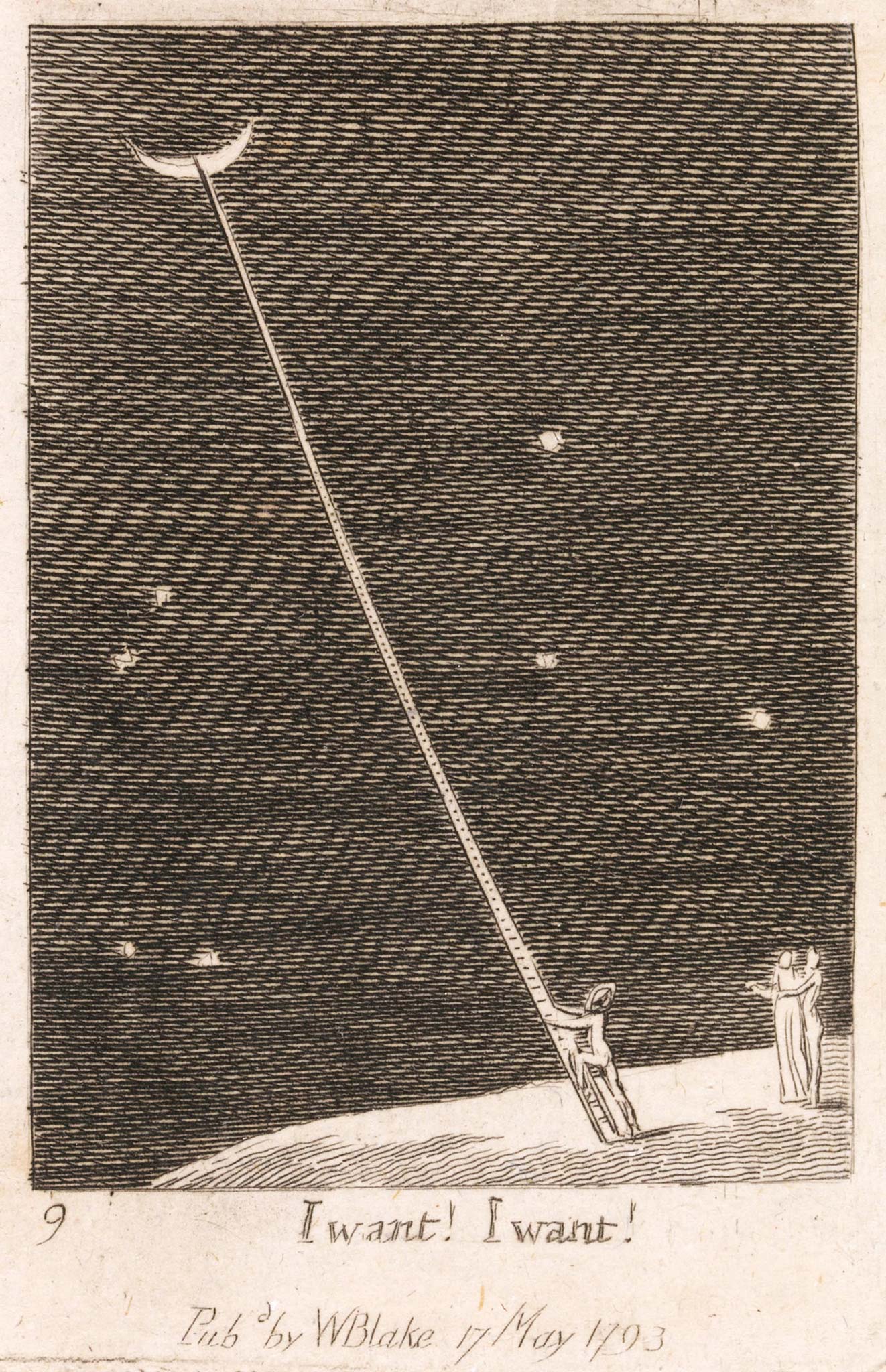

Albert Einstein remarked, “Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited to all we now know and understand, while imagination embraces the entire world, and all there ever will be to know and understand.” To Vassal, as to Einstein and Blake (cited earlier, in the Ascent image), nature is imagination. He finds that perspective liberating, in his work as well as in the rest of his life.

Some people may consider that view and other views of his to be overreaching or pretentious, as reductive as the junkiest science. But by his standards he neither reaches nor pretends. As I have said, other people may find his views incomprehensible, implausible, or nonsensical, but his experience affirms them, and they suit him.

They suit other people, too, including his friends and me. To our group, the meanings that they convey, ranging from aesthetic and philosophical to theological and spiritual, are substantial, often visceral, never merely intellectual—particularly now that his device is about to emerge so powerfully. Many of them have become touchstones as solid to us as anything we know. They pervade our lives. We are grateful to Vassal for them.

* * *

Before I met him, I, like many people, marveled at his invention’s possibilities. Also like many people, I developed an interest in him as a person. Who was this man? What was his life like? What did he think about? How did his mind work?

Most of the world, including me, learned about him after he returned from Europe with Victory. I followed news about him eagerly. I read about him in newspapers and magazines and watched programs about him on television. I talked about him with friends, colleagues, and students; the topic was a favorite. And as I have mentioned, I attended one of his and Victory’s live shows, and witnessed the public immolation of his last device.

I came to believe that I knew his views of the world, of life, of himself, and also—were he somehow to notice me—of me. Though I had not yet met him or communicated with him, I considered him a kindred spirit. I admired him for what he had invented and, particularly, for standing up to the government. To some extent, I confess, I worshiped him.

I was in my twenties then, a postpubescent female, sexually awakened. I found my professional life rewarding, but on the personal side I wanted an ideal partner, an intimate in both body and soul, who might help me live the best life I could. Like many people my age, I was not above entertaining fantasy lovers: TV and movie stars, rock musicians, professional athletes, handsome politicians, attractive work colleagues, hot guys in my neighborhood, etc. Vassal served as one of those for me. Since then, though I have not completely outgrown such fantasies, I have outgrown my yearning for Vassal’s or anyone’s sheltering embrace. But I have remained a devoted admirer, both of his accomplishments and of him as a person.

It must be evident to readers of this book that since he and I started working together ours has become a close personal relationship. His recent decision to revive his invention has bound us together tighter than ever. As I have said, one result of our long familiarity and compatibility is that often we share one mind. I feel that attunement most of the time, including when we are apart, or when he is doing something else, whether near me or not: reading, fishing, eating, puttering in the barn, chopping wood, etc.

Of course, I have not been alone in my admiration of him. From the start, when people first learned about his invention, many developed feelings similar to mine. He caused a potent genie to escape its lamp and enter their imaginations. That pleased them, and inspired their love and respect for him. No doubt many of them retain those feelings, along with their fond memories of him from the old days. Today’s return of his invention will excite and please them and revive their interest.

* * *

Vassal has conceived strong ideas and lived with them. He has tested them, refined them, and evolved with them. In the course of our project, he has articulated many of them to me, for me to transcribe for our books, primarily this one. Though he has not tried to persuade me to adopt them, they have influenced me. During my first years working with him, I sometimes felt overwhelmed by them. Despite their attractiveness, his presence in my life made it hard for me to open myself to them. I felt unsure of my boundaries, my selfhood. I blamed him for that. But I blamed him only in my mind, never to his face. I knew that my feeling was unfair.

I stopped blaming him long ago. I learned to consider his ideas on their merits and not confuse them with his person. I began to feel, as he did, that anything that bothers any of us is us bothering ourselves. Rumi wrote, “The fault is in the one who blames. Spirit sees nothing to criticize.” Also: “Every enemy is your medicine. . . .” I realized that any negative thoughts, feelings, and fantasies I had about Vassal were my own about myself. I was victim not of him but of my interpretations of him. I should not hold him accountable for those.

Everyone is

Jesus

Moses

Buddha

Mohammed

God and gods

risen or fallen

devils demons

you name it

Everyone is

everyone too

and every

creature

and thing

every cross

that you bear

nail in your flesh

spear in your side

and every wonder

miracle and blessing

All of that your typical

long-term love affair in

which nothing is ever wrong

except your understanding

* * *

It remains to be seen whether people will accommodate his invention and its implications as agreeably as I have, or with what some may call my cultish, star-struck, and love-struck submissiveness—an assessment of me that I would dispute. Whatever the nature of my cooperation with him, or of anyone’s admiration for him, his invention is nothing to fault him for. I agree with him that it embodies each and all of us, that it is at once us and apart from us, both self and an instrument of self, for each of us to inhabit as we and it will. That binary nature is everyone’s, not just his.

“Our machines are our fellows,” he says. “We master them only to the extent we master ourselves, which is not much.”

As with any tool, the possibilities of his invention will constrain us. We will have to conform to it and work within its limitations. In that sense, we will do its will. But its will will also be ours, a living part of us. To Vassal, not only are all things alive, no matter how inanimate and insensible they seem, but they also give rise to each other. Their birth never ends: mine, his, everyone’s, everything’s. Being pours forth from all quarters and flows free, comprising all known realities and then some.

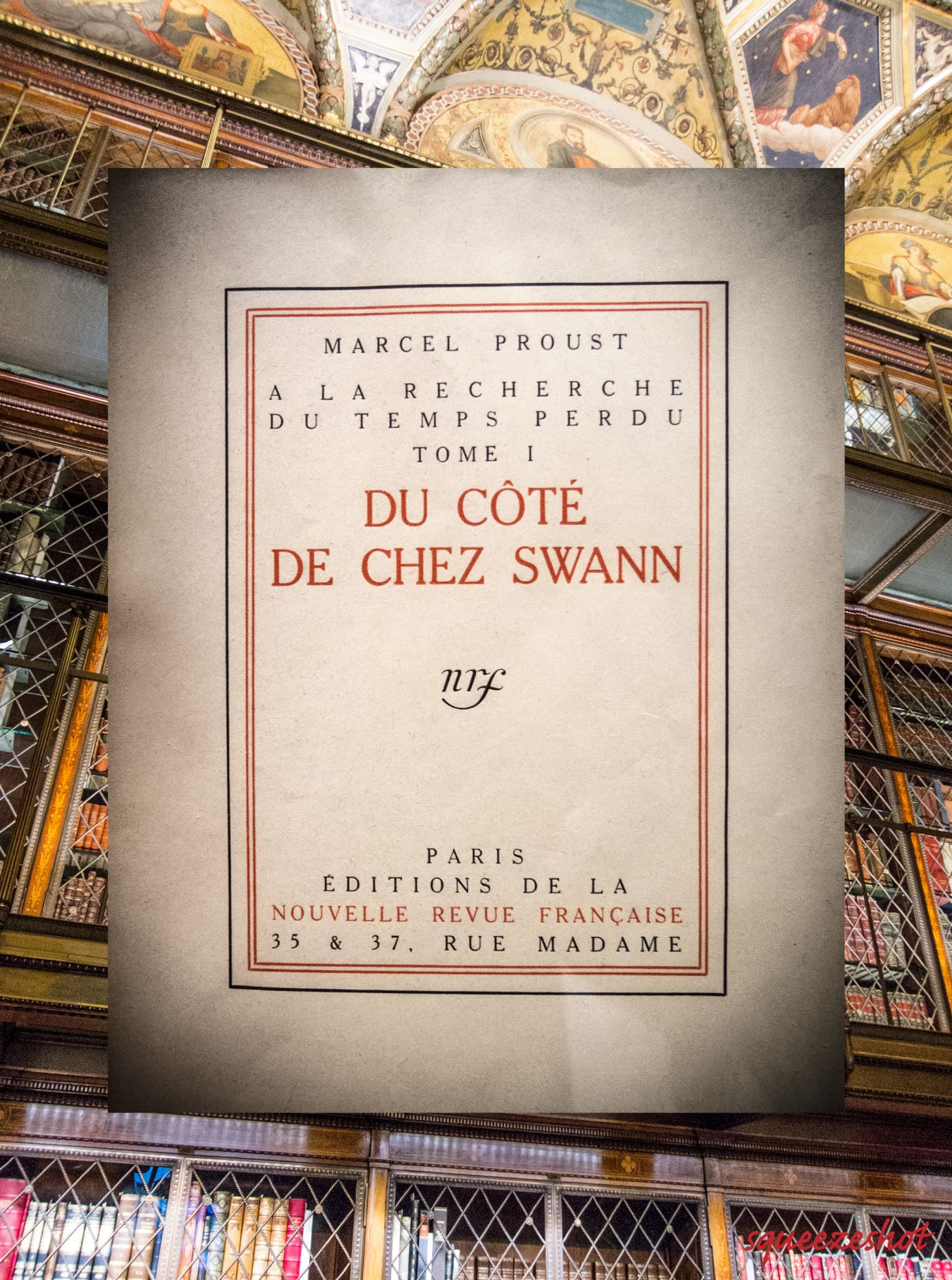

There is always more to life than we know. Marcel, in Proust’s Swann’s Way, upon awakening in the middle of the night, said, “Perhaps the immobility of the things around us is imposed upon them by our certainty that they are themselves and not anything else, by the immobility of our mind confronting them.” (Lydia Davis’s translation)

When something lifeless moves—when dead leaves rustle in the wind, when rain or snow fall, when waves ripple across water, when a cloud changes shape or a fog lessens, or when our vision tricks us so that something we see only seems to move, or when something motionless catches our eye and imagination as if summoning our attention and declaring its significance—we may believe for a moment that it lives. Seeing such lifelikeness may alarm us, but it never alarms Vassal. He observes it with interest and curiosity. Again, to him, all things are we, alive and responsive, their present dynamic and their future unknown—no immobility possible, nothing to be afraid of.

![]()

Vassal’s understandings can seem strange or worse: outrageous, perverse, pathological, even diabolical, depending on one’s perspective. Now that he has turned his invention loose, they are likely to upset some people. But as I have said, a bit defiantly, they do not seem strange or worse to him and others. They are consonant with the traditions, religions, philosophies, and experiences of many people, among them the Bigheads, the Indians, and me.

They can be difficult to dismiss, whether or not one finds them agreeable. They defy easy summary. He is no cheerful Pollyanna or euphoric priest of nature, as some people might suppose. Nor is he a passive-aggressive nihilist, hyper-discriminating aesthete, or intrepid seeker after enlightenment. His boundaries are more fluid. He does not believe that certainty, moral clarity, or similar fixity are possible, nor does he wish that they were. He is not willful in his observations or pontifical in his pronouncements. He claims no authority, and does not regard himself as a model for others. He does not wish for people to agree with him or to act in accord with his views. To the extent people differ from him, either in their minds or his, he sees nothing objectionable. He revels equally in difference and agreement. He works and plays with both. He suffers them and celebrates them, as we all do. But in doing so he dances with them like a dervish, and resolves them toward bliss.

He is reasonable and deliberate, conscious of every step. He has to be, to be the master scientist, engineer, and technologist that he is. In his work, he adheres carefully to scientific methods. But he riffs on those methods, too. His habits of mind and behavior are not rigid. In all of his explorations, he questions his findings. He does not mind when other people dispute them, even if they do so for no good reason. He welcomes everyone’s responses, opinions, and analyses as readily as his own. To him, there is no good reason, and none better than any other. He is always looking for new points of entry and new paths, and he finds them everywhere.

I have reported that he has no agenda that he wishes to fulfill. He did when he was younger, but no longer. He is no combative culture warrior, left/center/right reformer, or us-versus-them bigot. He is no self-important ideologue, earnest moralist, or righteous fundamentalist. He is no evangelizing believer, dogmatic theocrat, or conscientious progressive. And he is no condescending rationalist or arrogant elitist. Nor is he a theist trying to channel divine sanction, or a humanist employing secular means in vain attempts to improve people’s lot, or a naive optimist who wants a better world and anticipates no less.

Rather, he is all of those and more. Not that he is a shapeless specter, or a force without direction, though in the openness of his mind he resembles those. His genial adaptability and reflexive uncertainty will strike some people as indiscriminate or relativistic. As they use his device and consider its source, that may discomfit them. But not much. Like everyone else, they will be so involved in what they are doing with it that they will give the matter little thought.

* * *

Most of us like to think that since some time in the past our kind has made dramatic progress: since the formation of certain tribes, sects, or nations; or since the Renaissance, Enlightenment, or Industrial Age; or since the advent of fire, metalwork, writing, agriculture, the printing press, the internal combustion engine, electricity, etc.; or since the beginning of the modern era, with its many technological and material advances; or since the coming of one or another transformative leader.

Because we perceive that we are alive and conscious and once were not, we may believe that such progress is ongoing, that it is happening now and will continue. As Vassal would say, that belief suits the creatures that we are. We strive to maintain it. We fear that without it we would suffer more than otherwise; our civilization might weaken and fall apart, even, and our species die out. To avoid such fates, we sustain a sense of our advancement, and hope that it will lead to a time when our kind will live happily ever after in lands of peace and plenty.

He observes that though a sense of progress is necessary to us, progress is illusory. Not that we make no advances according to some standards: scientific, technological, medical, economic, social, etc. Advances in those realms are quantifiable in our terms, and often cumulative, and in those respects undeniable. But they are never all they are cracked up to be, never altogether satisfactory, never the shining achievements we like to think. They may invigorate us at first, and seem to help us, but they are subject to early obsolescence. They feel like progress for a while, but before long they become norms from which we want to progress further. They and we have no choice but to ride our living edge—in the curl of the wave, the turning of the wheel. Always, much remains that we want to accomplish.

Vassal does not mind that futility of ours, nor does he find fault with anyone’s faith in progress. However, compared to most other people, he is more wary of our idealized purposes and destinations, including not only progress but also Heaven, Nirvana, salvation, enlightenment, eternal happiness, lasting peace, final conquest, ultimate victory, and similarly wishful goals and end points. He observes that they stem from our ongoing dissatisfaction with ourselves and our world; and that they are often accompanied by somber beliefs in our original sin and imperfection, and a sense that we are somewhat ill-favored, even accursed, engaged in more and greater struggle than we should be.

In his view, as much struggle as comes our way is necessary for us, and our idealizing of favorable ends is part of it. Like anyone, he, too, wants more of many things, frivolous and not: relationships, experiences, possessions. In his case, however, he wants more not because he thinks that acquiring and possessing more is good, right, or beneficial; or because once he obtains them he will think that he, anyone, or anything has gained. He wants more because like any human he cannot do otherwise. Our kind always wants more, and always has more in mind. For us, that is biologically necessary, part of what we are, something we have to do. We embody our want and are never done with it. We hunger for certain things and are embarked upon a lifelong quest to satisfy that hunger. Without that, we could not create and express, transact and profit, acquire and consume. We would not exist in any way.

* * *

Many prophets claim

That Heaven’s joys, though endless,

Are not twice the same;

— Richard Wilbur, in “Sir David Brewster’s Toy”

To Vassal, everything opens to question. He values such uncertainty for its promise and danger, and for its constancy. Franz Schubert’s trout in the water sings, “The Earth is incredibly beautiful, but it is not certain.” Or, an alternative translation: “The Earth is incredibly beautiful, but not as safe as we suppose.” (In the original, more poetic: “Die Erde ist gewaltig schön, doch sicher ist sie nicht.”) Vassal would revise that lyric to say that the earth is incredibly beautiful because it is not certain, and because it is not as safe as we suppose. For him, embracing uncertainty, opening everything to question, yields no less.

He does not hesitate to contradict himself. Despite his powers of reason, and because of them, he does not hesitate to be irrational. He does not prefer that there be no imperfection, inconsistency, confusion, misfortune, or other glitches in the world—even as he strives to overcome them, as we all do. Like everyone, he rides inconstant winds. Unlike many of us, however, he gladly accepts and even delights in their inconstancy. His life is a natural act of balance, and his work an intuitive exercise in testing and experimentation. He believes in good and virtue, as we all do, and takes moral and ethical stands, but he takes them lightly, with accomplished uncertainty. That is how he treads the hot coals, journeys through the rising flames, and otherwise traverses the void.

To him, again, opposites like good and bad and right and wrong entangle and define each other. You cannot have one without the other; therefore, each is the other. He finds traces of joy, and the possibility of more, in even the worst that comes: in the anguish of suffering, the bleakness of depression, the agony of pain, the finality of death. He believes that when the mortal moment arrives for any of us, whoever we are is good enough, no matter what our transgressions and failings have been. Rumi again: “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.” In that loving place there is no role for judgment, no need for justice.

* * *

He understands evil and other badness to be human. To him, both are necessary and irreducible. Though we all hope for better, there is neither need for nor possibility of better. There can be no redemption for us as individuals, groups, or species. And there can be no final day of judgment, in our favor or not, by any agency human or divine. He considers gods’ laws and adjudication, Heaven and Hell as earned afterlife, and the like to be concepts that we humans have contrived in order to manage ourselves. Such is our divine standing.

He does not live in fear of such judgment. When he was a teenager, he scorned laws, rules, dogmas, good manners, and similar constraints. He disdained people’s attempts to codify, apply, and enforce them; to institutionalize them; to indoctrinate everyone in them; and to otherwise embed them in everyone’s lives. He believed that they restricted us unnecessarily, that they benumbed our spirits and consigned us to rot.

Since then, he has become more accommodating. He remains skeptical of such constraints, and suspects that many of them are unnecessary, but he no longer disapproves of them. He sees that to some extent they facilitate our coexistence with each other. He also sees that many of us, especially those of us in positions of power and authority, believe that they do. He considers them unavoidable.

“Our species is selfish,” he says. “It has to be. We look out for ourselves, as individuals and as a species. In the process, we try to manipulate each other some, to control each other. That’s part of how we endure and prosper. Even at our most generous we can’t avoid being selfish. At some level, even our most heartfelt gifts to others, given with our best intentions and deepest consideration, wrapped in our love, compassion, and kindness, are as vain and self-serving as any narcissistic indulgence. They have to be. I no longer see anything wrong with any of that. We do the best we can.”

* * *

At this hour, the release of Vassal’s invention is a fait accompli. Soon, millions of us will pick it up, imagine things that we might do with it, and then do them. As we use it, we will see and hear more than we have ever thought possible. That will challenge us not only as individuals; it will challenge our families, communities, organizations, and other groups. All will have their hands full explaining themselves and changing their workings, which will have become visible to everyone.

“Think of all the meetings and conversations that take place within businesses, governments, and other institutions,” Vassal says. “Think of all the documents, records, proprietary formulas and methods, and so on. Until now, most of those have been secret or at least private. Now, every interested party—every insider and outsider, including every employee, customer, competitor, regulator, journalist, and scholar—will have access to them. Imagine the consequences!”

As I have remarked, I am anxious to see what governments will do. Their reactions could be fierce. Starting in the next few hours they will rush to deal with what Vassal has done. Panic and rage will surge through their offices. He and I, the Bigheads, and our supporters and accomplices could get arrested, prosecuted, and imprisoned; or harassed or assaulted; or worse, as happened to Victory. Or not. Nothing of the sort may happen. The transparency that his invention will bring may protect us. Vassal’s history with the government leads me to hope.

Much of that history, like most of his story, is well known. He recounted it in the Journal, and it has been reported exhaustively elsewhere in the public record. But there is more of it that I should reveal. I should describe more fully some of his attitudes, opinions, and understandings concerning politics and government, as well as of his broader assessments of society. They shed light on his decision to release his invention, and on how he and others will regard its consequences. I will describe their origins and development, particularly in his adolescence. I will also describe how they have evolved since then, and shaped his path to the present hour.

SCROLL 6 ➡︎

TOP⬆︎

CONTACT/SUBSCRIBE

(See the latest newsletter here.)