THE SQUEEZESHOT SAGA

Description

PRELUDE CHORUS JOURNAL

The Society Shots

PRELUDE

by

The Reverend Professor Henrietta A. ( * )

A prelude to everyone’s future

PRELUDE is available in four formats:

- here on the web (it follows below);

- a PDF;

- a free “Made for iBooks” enhanced ebook, which you can download at Apple Books and add to your library;

- or you can print it from any of those.

![Apple Books badge]()

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Scroll 1

INTRODUCTION

IT

Scroll 1

CHAPTER ONE

OUT

Scrolls 1 2 3 4 5 6

CHAPTER TWO

OUTWARD

Scrolls 7 8 9 10

CHAPTER THREE

OUTERMOST

Scrolls 11 12 13 14 15 16

CHAPTER FOUR

IN

Scrolls 17 18 19

![]() AUDIO

AUDIO

The beginning of PRELUDE (14:22), read aloud by the real author:

PRELUDE

by

The Reverend Professor Henrietta A.

Scroll 1

to VICTORY

and to all,

as she would wish

if she were still alive

PREFACE

Arrived suddenly, hasn’t it, in your life and everyone’s—BANG! Quite a shot by Vassal, a delight to some and a shock to all. He and I have created this book and the rest of the Squeezshot Saga to accompany it. May you enjoy.

— H.A. (The Reverend Professor)

You Are All — Other Is You

You Are All — Other Is You

“. . . from all the borders of itself, burst like a star:

for here there is no place that does not see you.

You must change your life.”

— Rilke

It springs once again from the absurd and restless mind of Vassal Squeezeshot. He kept it within him for decades. We thought that it would die there. But now he has done what most of us would not: He has revived it and turned it loose, allowed it to escape his sanctuary. It is reborn, this time to all of us. It is getting at us, and we at it.

We begin at a distance, as its audience. We stand together, lean toward it, and squint to see. How much of it has he rebuilt? Is it the same as it was? Has he changed its powers? Last time it was tiny, wireless. It could fly anywhere at his command, cross any border and enter any room. It could watch and listen to anything, and transmit to him everything that it saw and heard. This time it will be similar, we expect, able to do as much, maybe more. But we do not know, not yet. We cannot make it out, cannot be sure that it is what we think it is. But it must be; it comes so much the same: its monstrosity, its sudden eminence, its charm.

Even far away, it looms. Will it do what it threatened—or promised—last time, what it could have done but did not: alter our senses of ourselves and each other; change how we think, feel, and behave? If so, will that be good for us, or bad? Will it lead us to glory, or to loss? And why after so many years has he decided to give it to us? He suffered so much because of it. He understands the risks so well. Why does he wish them upon us? What is he thinking?

We peer at it. What beast is this? Is it the thing itself, small as a mosquito, which he could hold between his thumb and fingertip? Or more its aura, penumbra of our fear and hope, shadow cast by light unseen? It acts alive: It wanders, pivots, changes direction. Is it searching? For us? It stops, tilts—forward, we presume—and steps ahead, as if onto a surface. It steps again, faster, and breaks into a run. It curves one way then another, as if unsure. Then it finds its mind, or it seems to; it speeds up, and carves a turn until—

It is coming right at us. It wobbles, steadies itself, and accelerates more. It runs hard; its muscular strides stretch across the distance. Or it comes more compact; it rolls, bounces, and bustles, in cursive hurry. Or it touches nothing, flies straight and true as simplest thought—zzzzzap!—as if it occupies less than a single dimension. Or it comes low, scraping the earth in a zigzag skid, unruly and unpredictable as the dragging butthole of a shit-itchy dog.

Or what? What else? What other? We do not know. It confounds us. It demands more clairvoyance than we possess. We know that not all that is real is visible. We know that like anything it may be illusion. But we do not know enough, our senses do not tell us more, and our imaginations fail us.

* * *

It rushes onward. Does it stir up dust? Is there ground beneath it? Or does it approach us from on high, borne through the air like one of Vassal’s angels? Or come solitary, naked, stark as a jewel, a burning light, an infant that writhes in vast and immaterial space?

Yes, that’s it. It is an infant, a stomach with a brain, desirous of every mother. See it stare. Is it staring at us, or only we at it, or we at ourselves? All three, I would not doubt. We are facing points of view, a chorus of It. Its possibilities converge and combine, in flux. It is wave as much as it is object, and idea as much as either. From what sea does it swell? What ocean does it o’erflow? What impels its flood unspeakable? What sends its surge to our backward flowing river, to wash our contrary tide? We can suggest answers, but we cannot say for sure.

We must confront what appears. We must summon what knowledge of it we can, and make do. It is coming at us head-on, so that it appears foreshortened; we cannot judge its distance from us. But we do not doubt its speed, strength, and fury. It seems increasingly vivid to us, as if soon we will make sense of it. We want to jump ahead in time, bring it near, see it whole, and know what its impact upon us will be. But we cannot. We cannot act, cannot move. We can only remain where we are, in its path. We are disarmed and unready; incapacitated as if by sleep, injury, or death; bemused, perhaps, by a perverse contentment, some complacency from which we have not awakened.

* * *

Our feeling changes to dread. We are on our own with it, each of us. We want to see it gone, be free of it, but that is impossible. It is not going away. It is attacking us, and we cannot avoid it. We live at its mercy, like lambs before the knife. Its imminence narrows our focus and sharpens our view. We see no kindness in it, no consideration, no sign that it even perceives us, much less that it recognizes us or cares about us. It seems to come at us without purpose, by coincidence, unintended by any agency, its own or any other’s.

It keeps coming. It does not slow down. It is almost upon us, about to hit us. We fear that we are facing a mortal blow. We tense every muscle, and cast our minds away. It races to our feet, where it—

It stops. We recoil. We cannot move our legs; we may fall over backward. We twist, teeter, bend, wave our arms, like clowns at a precipice. We remain standing, but barely. We look down. It has stopped inches away from us. It does not move or make a sound. We do not dare to breathe. We look more closely. We see a beast of vague boundary, still no detail.

It moves. We see legs, muscles, paws, claws, or we think we do. It gathers itself downward and presses into the ground, as if prostrating itself to us. Now we see no legs or paws, no body, and still no head or face, but we see eyes or what pass for them: shapes that shine within shapes. Does it see us? Does it know us? We cannot tell. It may possess senses as keen as ours, or it may possess none, its eyes inert, ornamental, able only to reflect us back to ourselves.

We are afraid. We fear that it will rise up, seize us, and carry us away to we know not where. Or that it will knock us down, spill our blood, rip at our vitals, and devour us, strewing our bones, hair, teeth, nails, and remnant scraps of flesh across memorial earth. We want desperately to plumb its mysteries and gauge its intent, but we cannot. We can only continue to ask ourselves: What creature is this, and what might it do to us, and when?

* * *

Our fear is not all that blossoms. Sound, too, slides through. We hear a hiss of inhalation. The creature is alive, or it may be. Or is that sound our own? We watch and listen more. It moves again, expands and contracts as if breathing. Or is that, too, a product of our fevered attention? We perceive its mass and we feel its momentum. It appears more solid to us than anything we have ever seen, more real than what we call reality, as undeniable as words on a page. But still we do not know what it is, whether it lives, and what it may do. No evidence accrues, no science applies; our senses are too weak and our concern too great.

It remains at our feet, almost touching us. Might it kill us? Has it killed us already? We wait and we watch, doubting everything, until—

It leaps, closing the gap. It sprawls upon us and embraces us, immersing us in our amazement. It pierces us, penetrates us, enters us, and uncoils within us. Its warmth combines with ours. Our minds commingle with its strangeness. We confuse everything—self with other, ours with its—like lost children in search of the familiar. Where will that end? Are we regressing toward infancy and birth, the womb, the egg and sperm? And then?

It has struck us hard, but the pain we feel is negligible. Our disorientation has grown faint. We are falling toward sleep. Or toward death—are we about to die? We are not unhappy, but we wonder whether we should try to stay awake, and whether we can. Alarm stirs within us, and rings out calamity, but we cannot hear.

* * *

It ends. We move. In a dream or not, we open our mouths to scream. We raise our hands in self-defense, and lean back over our heels, as if to lie flat and disappear. But nothing remains of us. The beast has become us, our faces its masks. Our actions have become gestures: vacant, vestigial, without intent if they are happening at all. We do not know anything, ourselves or any other. Our thoughts lie empty, our memory gone, all husks of remembrance fallen away. Our bodies and minds have changed without direction. Our hopes have vanished, and we do not miss them. We do not miss anything that is absent.

Mind everyone’s mind

does what it always does

It looks in looks out

doesn’t look

never looks

It sees everything

and more always more

And it sees less too always less

less than anyone can imagine

less than words can say

less than nothing

An hour before dawn, Vassal Squeezeshot and I drift in starlight through the river’s mouth. We stand together in our boat and look upon shadows. The current runs silken, black. It muscles past the whirlpool eddy, sweeps skinless around the last stone point of land. The old fort hunkers at the edge, in mist this August night. The block walls glisten. The iron gun ports molder. At the other shore, three hundred yards opposite, granite ledges bruise the flow, lie dark against the jitter of water. Beyond them, a forest of evergreens rests on its carpet of earth. The boughs of spruce, fir, and pine trees hang motionless. They shelter gloom and counsel sleep. We cannot sleep. We have been awake all night. We may stay awake for days.

Vassal murmurs to me, “Now that we’ve done the deed, Reverend, we may not rest much. We may not want to. We may not be able to.”

I look up at him. I see only his silhouette. It towers against the stars. He could be a cloud overhead, a storm brewing. Or he could spread more distant, among the galaxies, a being so massive that no light can escape him. Later today, when people everywhere discover what he has done, they may believe no less. But he is no such thing. I can attest to that. I have lived and worked with him for more than thirty years, since the 1980s, when his story last led the news. I would have noticed. He is human, neither more nor less. He is unusual, certainly, but who isn’t?

* * *

Today, he is giving his invention to the world, distributing it to millions of people, in every country, for free. They will find it during the next few hours, as they awaken and go about their lives. They will take it up and use it. Word of it will leap like flame from person to person, and from social and news media. People who do not have one yet will want one. He has arranged that anyone will be able to get one. Soon, everyone will have one and be using it.

WHAT IS IT?

Most people already know what it is and what they can do with it; they remember from last time, or they have learned about it since. For any who do not know or who want reminding:

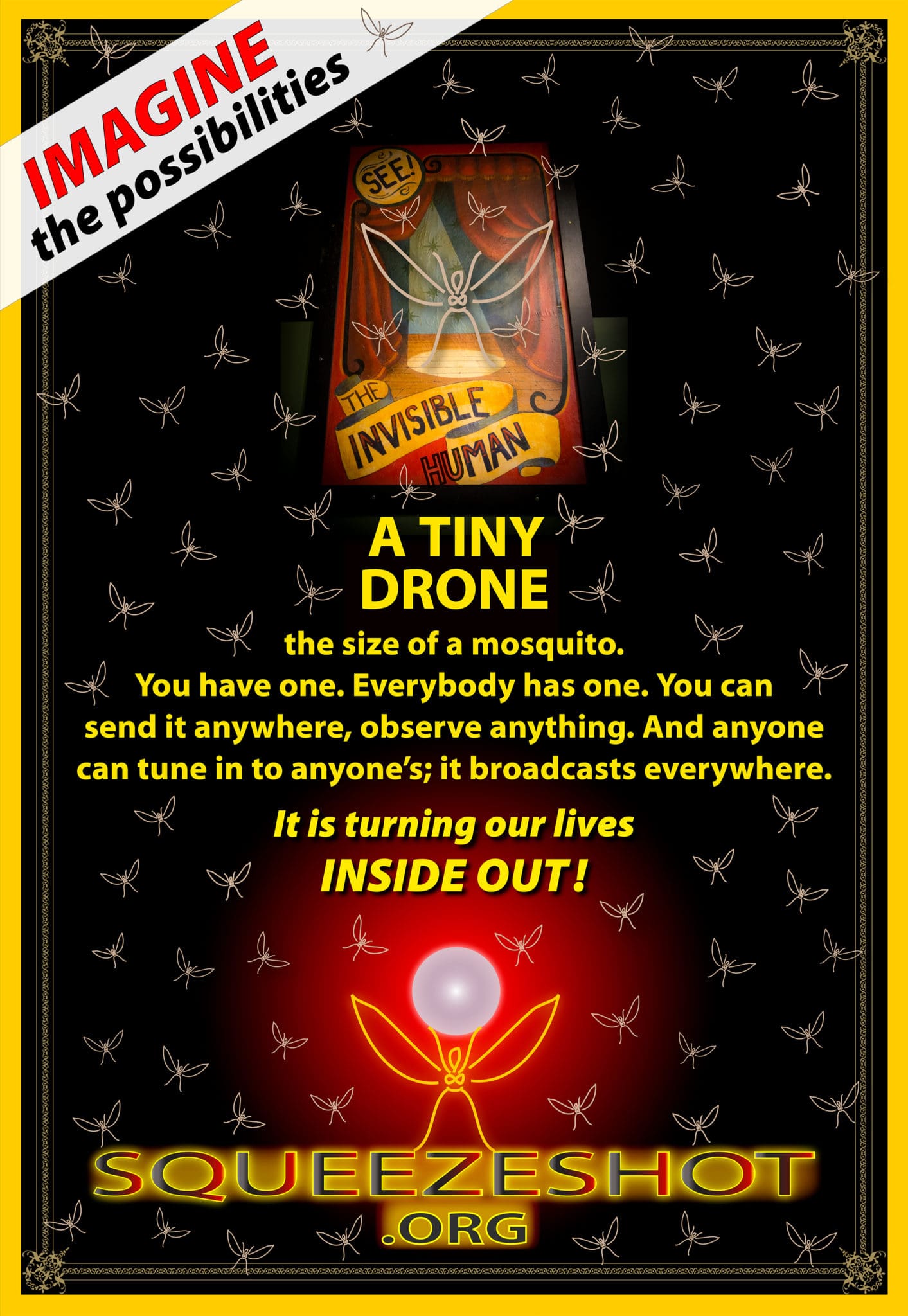

- It is a tiny drone, a robotic fly. Its system consists of two units, both wireless. One is the fly itself. In appearance, it resembles a mosquito. It has fiber wings that beat rapidly, enabling it to fly. And it has delicate, articulated legs, which permit it to land anywhere, or to hitch a ride on anything that moves. Because it is so small, it can come and go, and lurk, unseen.

- It incorporates a miniature video camera and stereo microphone, and a transmitter that broadcasts what they see and hear. It broadcasts over any distance, from across a room to around the world. The quality of its video and audio is so good that anyone who tunes in feels physically present wherever it is located.

- The system’s second unit is a receiver/controller. There are three versions. One, being distributed tonight, is headworn and looks like a pair of sunglasses. It displays to its operator what the fly sees and hears, and enables the operator’s voice, brainwaves, facial expressions, and movements of the eyes and head to control where the fly goes.

The operator’s voice, brainwaves, facial expressions, and movements of the eyes and head control the fly. (Model: Surgey, a Bighead, Prince of Perpetual Transfiguration)

The operator’s voice, brainwaves, facial expressions, and movements of the eyes and head control the fly. (Model: Surgey, a Bighead, Prince of Perpetual Transfiguration)

- The second version of the controller is a small box the size of a pack of playing cards. It connects wirelessly to computers, TVs, projectors, and mobile devices, and allows the operator to control the fly by means of touch, gesture, and voice.

- The third version is software-only, and integrates with most mobile devices and computers. All three versions are easy to use. After a little practice, the system feels like an extension of its operator’s mind and body. Even small children can use it, and no doubt will. Parents and teachers, beware!

- When the fly is turned on, it transmits what it sees and hears to everyone, not just to its operator. Anyone with a receiver can receive any fly’s broadcasts, no matter where it is or who is controlling it. People who use the system have no choice but to share with everyone what they see and hear.

- Any attempts to interfere with its broadcasts will fail. The system communicates directly from fly to receiver. It also communicates indirectly, via the Internet’s sprawling web of computers, networks, exchange points, undersea cables, and satellite links. Its use of the Internet is meshlike, decentralized enough to defy countermeasures. And if anyone even tries to impede it, computers—and, if need be, their human masters—will notice immediately, charge in, and negate the attempt. Resistance to it will be futile.

Its effects will range from innocuous to helpful to traumatic. Beginning a few hours from now, people everywhere will use it to observe anything they want. Our spouses, children, parents, friends, relatives, neighbors, and colleagues will watch and listen to us through it at any time, without our knowledge or consent. So will businesses, governments, police, researchers, marketers, salespeople, spies, voyeurs, curiosity seekers, and other strangers. And we will use it to watch and listen to them.

Because its network will gird the globe, and because anyone who wants to will be able to tune in, it will serve as a panopticon, exposing everyone and everything to “the censorial inspection of the public eye” (Edmund Burke’s phrase). It will put every visible and audible aspect of our lives on public display: work, family, friendship, romance, sex, solitude. Our selves, experiences, relationships, institutions—all will turn inside out, revealed as never before. Distinctions between public and private will vanish. Privacy, secrecy, and intimacy as we have known them will end. So may our sense of security. So may our sanity.

What will we make of that? Where will that lead us? Will our use of Vassal’s invention undo us, or will we use it to our advantage?

A particular concern of mine is that governments will struggle to adapt to the new reality. As many people know, the government has been protecting Vassal and me for years. In light of the new transparency, how will our government and others perform their functions, executive, legislative, and judiciary? How will their armed forces fight? How will their law enforcement, regulatory, intelligence, and other agencies do their work? They will face many complications. Vassal and I may bear nearer witness to their struggles than we would like.

* * *

ITS HISTORY

During his invention’s first years, Vassal kept a journal. It described his history in some detail. Many readers of this account know that history. Any who do not can refer either to that journal (about which more shortly) or this summary:

- When he was a young man, his love of fly-fishing the rivers, streams, and ponds of the Maine woods led him to invent a robotic minnow, which he used to find and catch trout and salmon. That was the only use he put it to. He didn’t think about other things he might do with it.

- Soon afterward, he conceived and developed his robotic fly. His friends helped him: the Indians, who were his work colleagues; and his impish, thigh-high buddies, the Bigheads, particularly Jimmy the Fairy. The fly, too, he used only for fishing, to keep an eye on conditions at his favorite spots and to scout for new ones.

- Those were Cold War years. The U.S. was engaged in an arms and propaganda race with the Soviet Union. The Department of Defense and the CIA found out about his fly, wanted it for their own purposes, and came to him to acquire it. They assumed that they would have little difficulty, but he rejected their requests and offers, and ignored their pleas and threats. The Soviets, too, came and failed to persuade him. He did not think that either government should have it. He felt certain they would misuse it.

- Both governments continued to pressure him. Feeling harassed, he went on vacation to Europe. One night, on the coast of Normandy, in a World-War-II-era German bunker converted into a nightclub, he met another American, the avant-garde playwright, Victory Tree. They fell in love, and became partners. She was the first person—and until now the only person—with whom he shared his device.

- They returned to the States. The government sheltered and protected them, still hoping to acquire his invention from him, and to keep it out of enemy hands. After a few years, living at their home on the coast of Maine, they lost interest in it. Feeling that no one else should have it, they decided to destroy it, and did so.

- The government, though disappointed, did not want anyone to kidnap Vassal and force him to reconstruct what he had destroyed, so continued to protect them. A few months later, however, that protection failed; someone slipped past the government guards and shot Victory in the forehead, killing her. Traumatized, Vassal went into seclusion, where for the most part he has remained.

After Victory’s death, Vassal ceased making entries in his journal. Some months later, he decided that he should publish it for the world to read. He titled it Through the Eyes of God: The Battlefront Journal of Vassal Squeezeshot. Millions of us read it as soon as it came out, and millions more have read it since.

Decades later, it is still in print. Readers buy it online and in bookstores, find it in any library, and pluck used copies from tabletops and cardboard boxes at neighborhood yard sales. Now that Vassal is releasing his invention, demand for it will be greater than ever. People will want to read it again, more closely, or read it for the first time, hoping to find it relevant to the new circumstance. With that relevance in mind, he and I are updating it, completing a second edition. Until we publish it, we are posting fresh excerpts at the saga’s website.

For several years after he published the original edition of his journal, Vassal’s story was widely reported in print and broadcast media, and was a prime topic of conversation. In addition to the Journal, people read dozens of other books and articles about it. Several of the books stayed on best-seller lists for years, with the Journal. Two won Pulitzer Prizes. People also flocked to two Oscar-winning films based upon it, one a documentary and the other a Hollywood blockbuster. Both films set box-office records, and became classics. As a result, without leaving his home in Maine, Vassal became a major celebrity and, to some people, an object of veneration.

Younger people, who have grown up since then, have learned his story from their elders. Parents still tell their children that they use his device to watch for bad behavior—a threat that may soon come true. Many children study the subject in school, as well. High schools and colleges, particularly, teach the Journal to students of history, government, and sometimes of English and writing, as a personal account and tale of adventure.

The story constitutes a modern myth. More than a generation later, it still comes up in homes and classrooms, and in the press, the arts, and political discussions. It holds a place in history, as a footnote to the Cold War and the social ferment of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Issues that it raised persist, including many that I address in this book.

The possibilities of Vassal’s invention have not ceased to intrigue people. Now, as he and I drift toward the new day, we are all about to fulfill some of those possibilities. At first, what will matter most will be the stunning presence of his invention in everyone’s lives. We will all scramble to deal with that, many of us feeling anxious to protect our interests and preserve our ways of life.

He and I understand the sense of urgency with which people will read this book. I plan to finish writing it this afternoon. We will publish it immediately. By evening, it will be on the saga’s website and elsewhere, and copies, excerpts, and links to it will begin to circulate online and in the press. It will describe what Vassal and I experience as today develops and people start using his device. It will also incorporate material that I have created in the past few months, in anticipation of this day. During my thirty-plus years with Vassal, I have spent much time observing him, and thinking about him and his invention. I have explored many facets of his saga, from many perspectives, suited to many people’s viewpoints. That has come naturally to me. I am a Reverend Professor, after all; I live an examined life. “Whatever pearl you seek, look for the pearl within the pearl!” wrote Rumi, the Sufi mystic and poet. So I have done, and so I love to do.

pearl

pearl

* * *

During my time with Vassal, I have witnessed some of his invention’s history firsthand. I have learned the rest from his journal, from other media, and directly from him. I have found that he is much more than a master scientist, engineer, and inventor. His outlook is broad as well as acute. He understands his invention’s implications, and he welcomes its possibilities, come what may.

I have sought to accommodate that outlook in this account. In addition to employing predictable genres such as memoir, biography, and in-the-moment narrative (“Vassal Squeezeshot and I drift in starlight . . .”), I have included much essay. That has allowed me to explicitly address topics that bear on the present situation. They include the effects of Vassal’s invention on our sense of self and other, and on our privacy and secrecy, love and compassion, morals and manners, freedom and responsibility, personal and collective security, and individual autonomy, as well as on our governments, religions, technologies, and more. Those topics are relevant to many readers, since they concern opportunities and challenges that in a few hours will be everyone’s. In these pages, I represent them as well as I can, and I suggest how to handle them.

In addition to my writing, to illuminate more than words alone can do, I have used my computer and camera to create images and illustrations. I will include those in these pages, along with one drawn by Vassal: his original sketch of his invention.

Some people, of course, will not have time, patience, or vision for any of that. They will be busy leading their lives, which from now on will include using Vassal’s invention and coping with other people’s use of it. If they visit these pages at all, they may stay only briefly.

Other readers will want a more complete accounting than this book will provide. Social and news media will begin delivering that today, no doubt. Anyone interested can also refer to resources I have mentioned, particularly the Journal. And soon, Vassal and I may publish more volumes, not just this one and the revised Journal. We have created and almost finished several. With this book and the Journal, they complete the inside story of his invention, and provide much meditation and discussion about it.

SCROLL 2 ➡︎

TOP⬆︎

*PRELUDE and its author/artist,

*PRELUDE and its author/artist,

The Reverend Professor Henrietta A.,

are fictional creations of Marcus Parsons.![]()

![]()